A visitor hesitatingly stands by a door of a room filled with folders, thickly bound papers, and books and in some places covered by dust. The guest wonders what they really are. A lady, Cecilia, gladly ushers in the visitor into the sanctum of the room and humbly says, “These are the works of my late father.”

This visitor sweeps his eyes from corner to corner with awe, for he is looking at the works of one man in a span of almost five decades. This man was Jose Cinco Gomez.

His works reveal his acceptance to the realities of life; his music brings a message to listeners that seem to say, “that’s it, my friend, life is full of joys and sorrows, but we must love life, for life is to love itself.”

Radiating from his composition is a vision of sacrifice, humor amidst adversities and contentment with one’s limitation in life. At times he veers towards musical painting, depicting the pageantry and gaiety of the “Waray” people as expressed in his “Harupoy Bukidnon” and “Hiboy-Hiboy.”

Many times Joe, as he was known in the region, received offers which could have given him fame and fortune. He turned them down for acceptance of the offer meant leaving Calbayog. To him, more than anything else except God and his family, Calbayog is his second love. This is sincerely expressed in his composition, “Calbayog.”

This visitor sweeps his eyes from corner to corner with awe, for he is looking at the works of one man in a span of almost five decades. This man was Jose Cinco Gomez.

His works reveal his acceptance to the realities of life; his music brings a message to listeners that seem to say, “that’s it, my friend, life is full of joys and sorrows, but we must love life, for life is to love itself.”

Radiating from his composition is a vision of sacrifice, humor amidst adversities and contentment with one’s limitation in life. At times he veers towards musical painting, depicting the pageantry and gaiety of the “Waray” people as expressed in his “Harupoy Bukidnon” and “Hiboy-Hiboy.”

Many times Joe, as he was known in the region, received offers which could have given him fame and fortune. He turned them down for acceptance of the offer meant leaving Calbayog. To him, more than anything else except God and his family, Calbayog is his second love. This is sincerely expressed in his composition, “Calbayog.”

In 1968, he reiterated his love for Calbayog. While a guest on a TV show, “An Evening with Pilita,” where the lady host sang his composition, “Goodbye,” with Joe himself on the piano, he was asked why he insisted on composing songs in Calbayog for many years. He was asked further if he had plans of coming to Manila. With a serious smile on his face, he humbly answered, “I don’t think there is any harm in composing more songs in Calbayog.”

Just as the whole life of Joe had been confined in Calbayog, so was his composition. They were merely for his self-expression. It was not surprising that in April 1974, when a movie director wrote asking for his permission and terms for the use of his “Inday Lolay” as musical scoring in “Sunugin ang Samar,” that, even if it meant a name for him, Joe politely refused.

“I have had enough praises,” he said. Gomez had never been affected by praises and accolades even at the time when his Cecilian Orchestra was invited to perform at Malacañang Palace in 1946 for the victory celebration of President Roxas and when the Cecilian Cultural Group which he organized sang before Miss Universe 1974 Amparo Muñoz and her beauty court at the Cardinal’s palace in Cebu City where after the performance Tourism Secretary Jose Aspiras immediately crossed the hall to congratulate him for his superb compositions and arrangements.

The praises served only as an inspiration for him to aspire for a better work than before and be worthy of those appreciation.

Joe’s unusual traits may be traced back to his parents, the late Licarion Gomez and Benigna Cinco, who in their lifetime were a simple quiet couple. Their eldest son, Jose, who was born on February 27, 1911 in Barangay Obrero (earlier popular as Barrio Tabok), Calbayog City, had carried on this simplicity.

Just as the whole life of Joe had been confined in Calbayog, so was his composition. They were merely for his self-expression. It was not surprising that in April 1974, when a movie director wrote asking for his permission and terms for the use of his “Inday Lolay” as musical scoring in “Sunugin ang Samar,” that, even if it meant a name for him, Joe politely refused.

“I have had enough praises,” he said. Gomez had never been affected by praises and accolades even at the time when his Cecilian Orchestra was invited to perform at Malacañang Palace in 1946 for the victory celebration of President Roxas and when the Cecilian Cultural Group which he organized sang before Miss Universe 1974 Amparo Muñoz and her beauty court at the Cardinal’s palace in Cebu City where after the performance Tourism Secretary Jose Aspiras immediately crossed the hall to congratulate him for his superb compositions and arrangements.

The praises served only as an inspiration for him to aspire for a better work than before and be worthy of those appreciation.

Joe’s unusual traits may be traced back to his parents, the late Licarion Gomez and Benigna Cinco, who in their lifetime were a simple quiet couple. Their eldest son, Jose, who was born on February 27, 1911 in Barangay Obrero (earlier popular as Barrio Tabok), Calbayog City, had carried on this simplicity.

Jose C. Gomez was exposed to music since his tender age. It was his father’s hobby to play the piano after each working day. As soon as he was through, the young boy would follow suit to tinker on the ivory keys. Seeking his interest in music, Licarion provided him with a tutor, Sofio Camilon and further exposure came when he played in the Colegio de San Vicente de Paul as a Banjo-playing character.

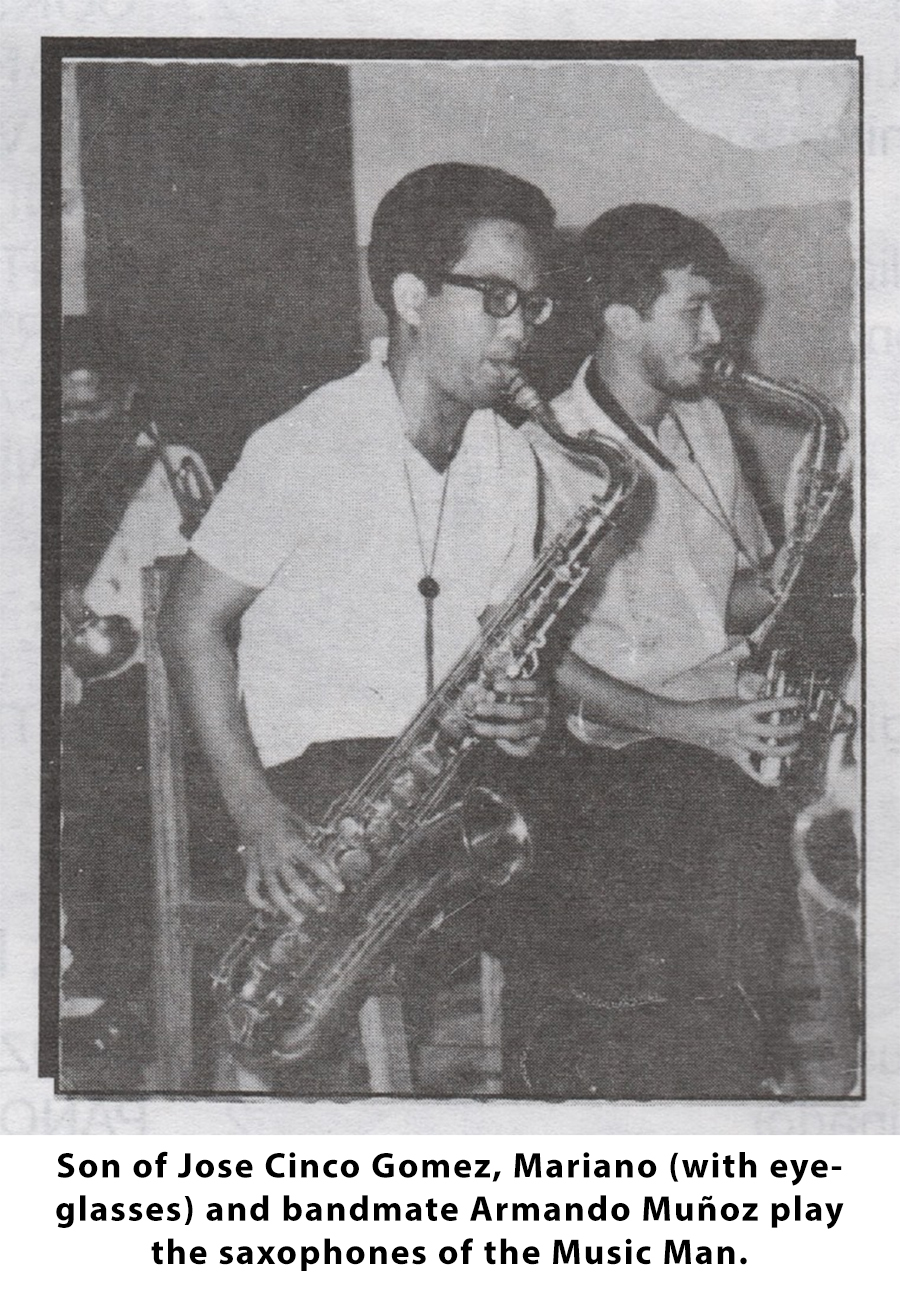

By this time, he already had acquired a “Musical Touch,” mastering any instruments his finger could touch on, including the saxophone he borrowed from his cousin, Antonio Gomez.

His interest expanded to musical arrangement and pursued it with the aid of an old family Victor phonograph. So he could identify distinctly the arrangement of each instrument on a particular recorded selection, he had his kid brother, Conrado, kept holding adjustment lever of the phonograph to maintain the “slow” speed while he took notes of his observations on papers.

By this time, he already had acquired a “Musical Touch,” mastering any instruments his finger could touch on, including the saxophone he borrowed from his cousin, Antonio Gomez.

His interest expanded to musical arrangement and pursued it with the aid of an old family Victor phonograph. So he could identify distinctly the arrangement of each instrument on a particular recorded selection, he had his kid brother, Conrado, kept holding adjustment lever of the phonograph to maintain the “slow” speed while he took notes of his observations on papers.

Arriving home in Calbayog fresh from Sta. Isabel Conservatory of Music in Manila, Miss Patricia Ortega (later married to Angelo Consunji) became the rallying point of local music enthusiasts, like Pablo Rueda, Crispulo Mandolaria, Jose Gomez and others. Through common interests, all decided to organize an orchestra calling the group “Cecilians” after the patron saint of music.

From thereon, Joe, at sixteen, started composing songs. He composed his first work, “Mirza” in April 11, 1927. He sent this composition to, then famous bandleader, Malaquias Nonato of the famed Philippine International Band based in Hongkong. The composition was returned with suggestions for improvement. This made Gomez depressed and dejected refusing to take his meals for weeks. After he was finally able to gather his senses, he took composition as a lifelong challenge. The recognition and praises of the Calbayognons showered to the performance of the Cecilians helped enliven the spirit of Gomez.

A shadow loomed over their unity at the height of their local success when Patricia Ortega got married that the youthful musicians seemed to have lost a rallying point. They disbanded.

Joe left to try his luck in Cebu. He found it by joining an orchestra, which was regularly playing at a decent nightspot, “Cebu Blues Cabaret.”

The orchestra owner, noticing immediately his musical talents, gave him a full freedom to compose, arrange and conduct his compositions as they play nightly at the cabaret. During this time he wrote “Phantom of the Blues,” “An Kabu” (which later became better known as “Awit San Cecilian”), “Dreamy Moon,” “Love at Last,” and many others songs.

His mother, however, had other plans. Concerned with his future, she requested him to return home and upon arrival told him to pack up for Manila for further studies. The proposal did not appeal to Jose. Instead, without any meaning to hurt his mother’s wishes, he revived the Cecilians. Now musically honed after his three years stint in Cebu, he knew where he stood. Joe was its bandleader.

Joe went on to gather fame without fortune and went places in Leyte and Samar with his well-known Cecilians. In performances, he cut an attractive figure on stage. Tall, dark and imposing, he kept the audience spellbound – specially the women – with his ubiquitous clarinet.

For all the feminine adulation, only one woman held him helplessly in a romantic fascination - Miss Francisca Soriano Lazaro of Sta. Cruz, Manila, who came to teach in San Policarpo Elementary School in 1932. Typical of a young man in love, Joe was never the same again since their meeting in a social affair at the residence of the late Senator Tomas Gomez, Sr. They were married on March 28, 1936. Years thereafter, six children were born: Cecilia, Antonio, Mariano, Virginia, Manuel, and Remigio.

From thereon, Joe, at sixteen, started composing songs. He composed his first work, “Mirza” in April 11, 1927. He sent this composition to, then famous bandleader, Malaquias Nonato of the famed Philippine International Band based in Hongkong. The composition was returned with suggestions for improvement. This made Gomez depressed and dejected refusing to take his meals for weeks. After he was finally able to gather his senses, he took composition as a lifelong challenge. The recognition and praises of the Calbayognons showered to the performance of the Cecilians helped enliven the spirit of Gomez.

A shadow loomed over their unity at the height of their local success when Patricia Ortega got married that the youthful musicians seemed to have lost a rallying point. They disbanded.

Joe left to try his luck in Cebu. He found it by joining an orchestra, which was regularly playing at a decent nightspot, “Cebu Blues Cabaret.”

The orchestra owner, noticing immediately his musical talents, gave him a full freedom to compose, arrange and conduct his compositions as they play nightly at the cabaret. During this time he wrote “Phantom of the Blues,” “An Kabu” (which later became better known as “Awit San Cecilian”), “Dreamy Moon,” “Love at Last,” and many others songs.

His mother, however, had other plans. Concerned with his future, she requested him to return home and upon arrival told him to pack up for Manila for further studies. The proposal did not appeal to Jose. Instead, without any meaning to hurt his mother’s wishes, he revived the Cecilians. Now musically honed after his three years stint in Cebu, he knew where he stood. Joe was its bandleader.

Joe went on to gather fame without fortune and went places in Leyte and Samar with his well-known Cecilians. In performances, he cut an attractive figure on stage. Tall, dark and imposing, he kept the audience spellbound – specially the women – with his ubiquitous clarinet.

For all the feminine adulation, only one woman held him helplessly in a romantic fascination - Miss Francisca Soriano Lazaro of Sta. Cruz, Manila, who came to teach in San Policarpo Elementary School in 1932. Typical of a young man in love, Joe was never the same again since their meeting in a social affair at the residence of the late Senator Tomas Gomez, Sr. They were married on March 28, 1936. Years thereafter, six children were born: Cecilia, Antonio, Mariano, Virginia, Manuel, and Remigio.

When war clouds gathered to begin the war years over Samar, Joe, then, in his thirties, was to demonstrate qualities of personal courage unexpected of a musician. Because of his demonstrated leadership in the community, he was appointed as an assistant supervisor for civilian defense for District One in Calbayog. That same year he became the Chief Deputy Municipal Air Raid Warden.

At the beginning of 1942, he was inducted by Captain Mariano Limas as an “operative” or secret policeman. As evacuees began streaming to Samar from Manila via Legaspi, he began to investigate the loyalty of the new arrivals. By June of that year, after having demonstrated such competence, he was formally inducted into the USAFFE and given the responsibility to organize and head the Secret Service Operations in the Calbayog area. With such position, in July of that year, he organized and headed three outlets for relaying messages – two from Calbayog City to Camp X in Mahalaga (now Malaga) and a third from Migara to Catarman. In October of the same year, he was summoned again by Lt. Suliman to Camp X for a conference concerning the counteracting of activities of lawless elements above Calbayog. This time, he was given the cloak and dagger designations as operative No. D-101.

Before Christmas of that same year, the musician lead a band which destroyed the Labuyao Bridge in order to cut the supply line of the Japanese between Calbayog and Oquendo. His sole support in this operation was just Corporal Pedro Cano armed with only one "Enfield" rifle.

At this point, Joe was to make a special contribution to the guerilla activity by joining with it his own particular gift for making music. Using his persuasive log, he moved the entire Cecilian band to join the guerillas.

In early February 1945, he went to the left river of Oquendo with the members of the orchestra to entertain the evacuees and to disseminate allied information in an attempt to build up the morale of the civilian population. In March of that year he was stationed again in Calbayog under the very noses of the Japanese to gather information on enemy movements. Again, Lt. Soliman called him for a meeting and in May ordered him to report to Barrio Kalagundian where he was assigned HQ 98th Regiment 93 Division of AUSA. On July 16th, after having a civilian volunteer he was called into active duty with rank of probationary third Lieutenant and assigned the work he like best, to conduct the Division. Here he was with old friends of the Cecilian Orcestra. Few guerilla groups could boost the fourteen-man band.

At the beginning of 1942, he was inducted by Captain Mariano Limas as an “operative” or secret policeman. As evacuees began streaming to Samar from Manila via Legaspi, he began to investigate the loyalty of the new arrivals. By June of that year, after having demonstrated such competence, he was formally inducted into the USAFFE and given the responsibility to organize and head the Secret Service Operations in the Calbayog area. With such position, in July of that year, he organized and headed three outlets for relaying messages – two from Calbayog City to Camp X in Mahalaga (now Malaga) and a third from Migara to Catarman. In October of the same year, he was summoned again by Lt. Suliman to Camp X for a conference concerning the counteracting of activities of lawless elements above Calbayog. This time, he was given the cloak and dagger designations as operative No. D-101.

Before Christmas of that same year, the musician lead a band which destroyed the Labuyao Bridge in order to cut the supply line of the Japanese between Calbayog and Oquendo. His sole support in this operation was just Corporal Pedro Cano armed with only one "Enfield" rifle.

At this point, Joe was to make a special contribution to the guerilla activity by joining with it his own particular gift for making music. Using his persuasive log, he moved the entire Cecilian band to join the guerillas.

In early February 1945, he went to the left river of Oquendo with the members of the orchestra to entertain the evacuees and to disseminate allied information in an attempt to build up the morale of the civilian population. In March of that year he was stationed again in Calbayog under the very noses of the Japanese to gather information on enemy movements. Again, Lt. Soliman called him for a meeting and in May ordered him to report to Barrio Kalagundian where he was assigned HQ 98th Regiment 93 Division of AUSA. On July 16th, after having a civilian volunteer he was called into active duty with rank of probationary third Lieutenant and assigned the work he like best, to conduct the Division. Here he was with old friends of the Cecilian Orcestra. Few guerilla groups could boost the fourteen-man band.

During this time, he was actively composing and to protect the authorship of his music, he obtained a letter from the adjustment General to submit to the headquarters of the 93rd Division to protect the copyright of all his musical compositions after the war.

The most tragic flow in his life came with the death of his kin and five members of the guerilla band who were captured by the Japanese soldiers in Barangay Acerida, Bobon, Northern Samar. Refusing to reveal the whereabouts of Lt. Gomez, his sisters Josefa, Francisca, and Trinidad were tortured by the captors. They were made to walk to Catarman - a 9-kilometer calvary. Josefa died along the way on March 7, 1944. Francisca and Trinidad reached the town only to be bayoneted to death at dawn of March 9, 1944, and buried in a common grave with five other members of the famous Cecilians - Corporals Basilio Comilan, and Maximo del Monte; Pvt. 1st class Pablo Aniban, and Irencio Jalayajay; and Pvt. 2nd class Ramon Aniban.

Although he refused to talk about the tragedy in later years, Joe, with bitterness still fresh in his heart, gathered enough strength to express the loss of his sisters in a heart-rending composition - “In the Wink of an Eye.”

For the people of Samar, these years were particularly difficult. Food was scarce. Joe was moved to write a song, “An Camote,” in praise of the lowly plant. Of it he wrote that even the poorest species, the Kabiruy, still is being eaten as it can cure acute hunger.

The leadership qualities which Joe Gomez had demonsrated during the war and the courage he exhibited, made him the logical person to organize and act as Chief of Police for Calbayog.

Calbayog was inaugurated as a city in October 16, 1948 (after the Republic Act declaring its creation as a city was signed in July 15, 1948). The following year, he took on the additional responsibility of being Chief of the Secret Service Division of Calbayog City police Department by Mayor Pedro Pido with a salary of PhP1,800.00 per annum. This arrangement continued until 1953 when he resigned from the Police Department. This was a turning point in his life when, to renew his musical activities, he put aside his police activities which he apparently enjoyed.

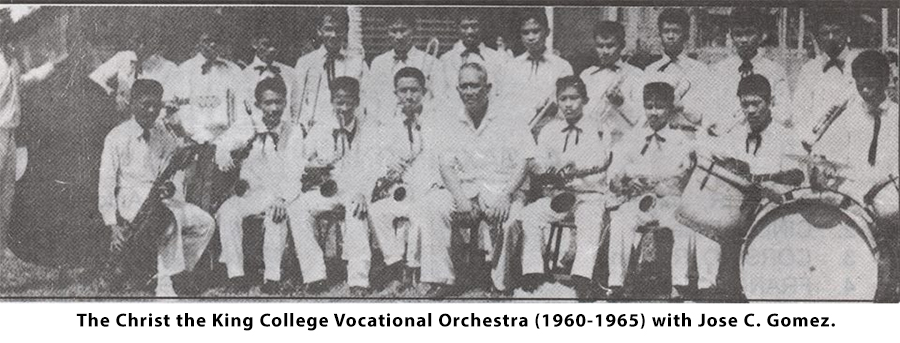

He was one of the first Calbayognons who helped the American Franciscan Fathers of the Assumption province (Pulaski, Wisconsin, USA) to establish a mission in Samar and took over the administration of Colegio de San Vicente de Paul. How successful he was is witnessed by a special letter of commendation sent to the administration of School Superintendent E. Santos who wrote “the new administration of this college should be congratulated and commended very highly for the successful training of some 70 high school boys and girls composing the college band, and in so short a time, a few modern pieces of ballroom dances as well as march music.”

The most tragic flow in his life came with the death of his kin and five members of the guerilla band who were captured by the Japanese soldiers in Barangay Acerida, Bobon, Northern Samar. Refusing to reveal the whereabouts of Lt. Gomez, his sisters Josefa, Francisca, and Trinidad were tortured by the captors. They were made to walk to Catarman - a 9-kilometer calvary. Josefa died along the way on March 7, 1944. Francisca and Trinidad reached the town only to be bayoneted to death at dawn of March 9, 1944, and buried in a common grave with five other members of the famous Cecilians - Corporals Basilio Comilan, and Maximo del Monte; Pvt. 1st class Pablo Aniban, and Irencio Jalayajay; and Pvt. 2nd class Ramon Aniban.

Although he refused to talk about the tragedy in later years, Joe, with bitterness still fresh in his heart, gathered enough strength to express the loss of his sisters in a heart-rending composition - “In the Wink of an Eye.”

For the people of Samar, these years were particularly difficult. Food was scarce. Joe was moved to write a song, “An Camote,” in praise of the lowly plant. Of it he wrote that even the poorest species, the Kabiruy, still is being eaten as it can cure acute hunger.

The leadership qualities which Joe Gomez had demonsrated during the war and the courage he exhibited, made him the logical person to organize and act as Chief of Police for Calbayog.

Calbayog was inaugurated as a city in October 16, 1948 (after the Republic Act declaring its creation as a city was signed in July 15, 1948). The following year, he took on the additional responsibility of being Chief of the Secret Service Division of Calbayog City police Department by Mayor Pedro Pido with a salary of PhP1,800.00 per annum. This arrangement continued until 1953 when he resigned from the Police Department. This was a turning point in his life when, to renew his musical activities, he put aside his police activities which he apparently enjoyed.

He was one of the first Calbayognons who helped the American Franciscan Fathers of the Assumption province (Pulaski, Wisconsin, USA) to establish a mission in Samar and took over the administration of Colegio de San Vicente de Paul. How successful he was is witnessed by a special letter of commendation sent to the administration of School Superintendent E. Santos who wrote “the new administration of this college should be congratulated and commended very highly for the successful training of some 70 high school boys and girls composing the college band, and in so short a time, a few modern pieces of ballroom dances as well as march music.”

He loved music so much that he relentlessly composed and meticulously wrote lyrics. He had preserved and collected age-old songs from he remotest Samar barrio polished them and in instant the lyrics were vague and loose, he fittingly supplied the lyrics but reained the original tunes like the “An Iroy Nga Tuna.” He had thousands of musical pieces, his compositions ranged from church hymns, Guerilla marches, Graduation marches, La Milagrosa March, Calbayog Pilot Central School March, TTMVS March, The CKC Hymn, “Christe Regians,” to love songs to songs about simple folks like the “Bongto Ko,” and Mutya San Kagab-ihon,” which won the first prize in the CIDAL meet singing competition in Catbalogan, participated by different schools throughout the Region VIII, Christmas songs, the “Panarit No. 2, 3, and 4.” In between, he composed 5,000 songs in his lifetime, 500 of which he applied for copyright, bookbound in his “Showers of Musical Thoughts.”

After more than a decade with the college faculty, Joe resigned and returned to a life of recluse, but feverishly devoting his time to composing and arranging songs. Desiring to preserve the cultural heritage of Samar and Leyte, he organized the Cecilian Cultural Group composed of teachers, lawyers, priests, local journalists, and radiomen and one talented street sweeper.

After more than a decade with the college faculty, Joe resigned and returned to a life of recluse, but feverishly devoting his time to composing and arranging songs. Desiring to preserve the cultural heritage of Samar and Leyte, he organized the Cecilian Cultural Group composed of teachers, lawyers, priests, local journalists, and radiomen and one talented street sweeper.

In September 1974, when he was sixty-three, Joe winner of “Paligsahan Sa Musika ’74 Songwriting Competition” for his composition, “Hiboy-Hiboy” in the municipal level (September 6-8), as well as in the provincial and regional sets (September 13-22). However losing to Dodong Pinedero in the Grand National Finals held at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) on September 25, 1974, the musician in Joe proudly said, “Even if I didn’t win first prize, I am, at least, one of the top musicians, being number one composer of Region 8 and rank 11 composer of the country.” The distinction was no small accomplishment for a man whose musical training was by correspondence, self-study and who had to dip his saxophone in a pail of water just to make it play.

THE END – THE FINAL NOTES:

Burdened with dreams yet unfulfilled, anxieties caused by his lonely fight against a Manila recording company in seeking redness for violation of his patent right for his composition, “Ahay,” a stroke set in on November 1974. The stroke rendered his left arm paralyzed – a fateful sign that he can no longer play the piano. He was brought to Manila for medical treatment.

On Christmas eve of 1974, meant to be his last, eldest son, Tony (pet name for Antonio) who just came from a party, happily barged in to his father’s room showing the elder Gomez a plaque and told: “I received this for my outstanding services to the company I worked for.” Carried away by his emotions, he further said addressing his father, “Pa, did you receive a plaque of recognition for your musical efforts in Calbayog?”

Rendered speechless and motionless with what he heard, Joe turned his gaze away from his son and stared pensively towards the window as tears slowly flowed down his aging cheeks. It was too late for the son to realize he triggered, in his father, the pain caused by frustrations.

Over the advice of the doctor and the wish of his family, Joe insisted on going home believing he would recover in Calbayog. He was home in Calbayog on January 1975.

That same year, on the second day of February, the month Joe was born 63 years back, death came and snuffed the life off of Jose Cinco Gomez just like a “Wink of an Eye.”

Jose Cinco Gomez was accorded seven awards for his contribution in the field of music but which he had never seen in his lifetime. All of the seven awards were posthumous. Wondering why things turned out the way it did will perhaps be aptly answered by the prolific words of the late Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: It is only when the time has gone that we know its message was divine.”

THE END – THE FINAL NOTES:

Burdened with dreams yet unfulfilled, anxieties caused by his lonely fight against a Manila recording company in seeking redness for violation of his patent right for his composition, “Ahay,” a stroke set in on November 1974. The stroke rendered his left arm paralyzed – a fateful sign that he can no longer play the piano. He was brought to Manila for medical treatment.

On Christmas eve of 1974, meant to be his last, eldest son, Tony (pet name for Antonio) who just came from a party, happily barged in to his father’s room showing the elder Gomez a plaque and told: “I received this for my outstanding services to the company I worked for.” Carried away by his emotions, he further said addressing his father, “Pa, did you receive a plaque of recognition for your musical efforts in Calbayog?”

Rendered speechless and motionless with what he heard, Joe turned his gaze away from his son and stared pensively towards the window as tears slowly flowed down his aging cheeks. It was too late for the son to realize he triggered, in his father, the pain caused by frustrations.

Over the advice of the doctor and the wish of his family, Joe insisted on going home believing he would recover in Calbayog. He was home in Calbayog on January 1975.

That same year, on the second day of February, the month Joe was born 63 years back, death came and snuffed the life off of Jose Cinco Gomez just like a “Wink of an Eye.”

Jose Cinco Gomez was accorded seven awards for his contribution in the field of music but which he had never seen in his lifetime. All of the seven awards were posthumous. Wondering why things turned out the way it did will perhaps be aptly answered by the prolific words of the late Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: It is only when the time has gone that we know its message was divine.”

NOTES:

-The information contained in this sketch were obtained from several sources.

-Jose Gomez left to the Divine Word Museum fifteen (15) typewritten pages containing autobiographical details; samples of his collections of proverbs, riddles, superstitions, translations of his two songs, “Ahay” and “An Camote;” and true copies of three letters of recognition from other sources.

-In addition, the late Conrado Gomez, younger brother of Jose, was interviewed personally by the writer on August 13, 1977, the wife and three children on August 14, 1977.

-From the typewriter of Jose Cinco Gomez are two pages of notes entitled “The Division Band” in which he describes the experiences of the Cecilians during the war and another two pages entitled “Main events in Life of the Cecilians” their early formation.

-Another source is a 2 page sketch from Mr. Jose R. Pandong, “MUSIC LIVES ON, JOSE CINCO GOMEZ,” Souvenir program of Calbayog City Fiesta, 1977; and a five-page sketch from Fr. Raymund Quetchenbach, SVD, Ph.D., Leyte Samar Studies Vol. XI No. 2 entitled “JOSE CINCO GOMEZ, THE MUSIC MAN OF SAMAR.”

-The information contained in this sketch were obtained from several sources.

-Jose Gomez left to the Divine Word Museum fifteen (15) typewritten pages containing autobiographical details; samples of his collections of proverbs, riddles, superstitions, translations of his two songs, “Ahay” and “An Camote;” and true copies of three letters of recognition from other sources.

-In addition, the late Conrado Gomez, younger brother of Jose, was interviewed personally by the writer on August 13, 1977, the wife and three children on August 14, 1977.

-From the typewriter of Jose Cinco Gomez are two pages of notes entitled “The Division Band” in which he describes the experiences of the Cecilians during the war and another two pages entitled “Main events in Life of the Cecilians” their early formation.

-Another source is a 2 page sketch from Mr. Jose R. Pandong, “MUSIC LIVES ON, JOSE CINCO GOMEZ,” Souvenir program of Calbayog City Fiesta, 1977; and a five-page sketch from Fr. Raymund Quetchenbach, SVD, Ph.D., Leyte Samar Studies Vol. XI No. 2 entitled “JOSE CINCO GOMEZ, THE MUSIC MAN OF SAMAR.”