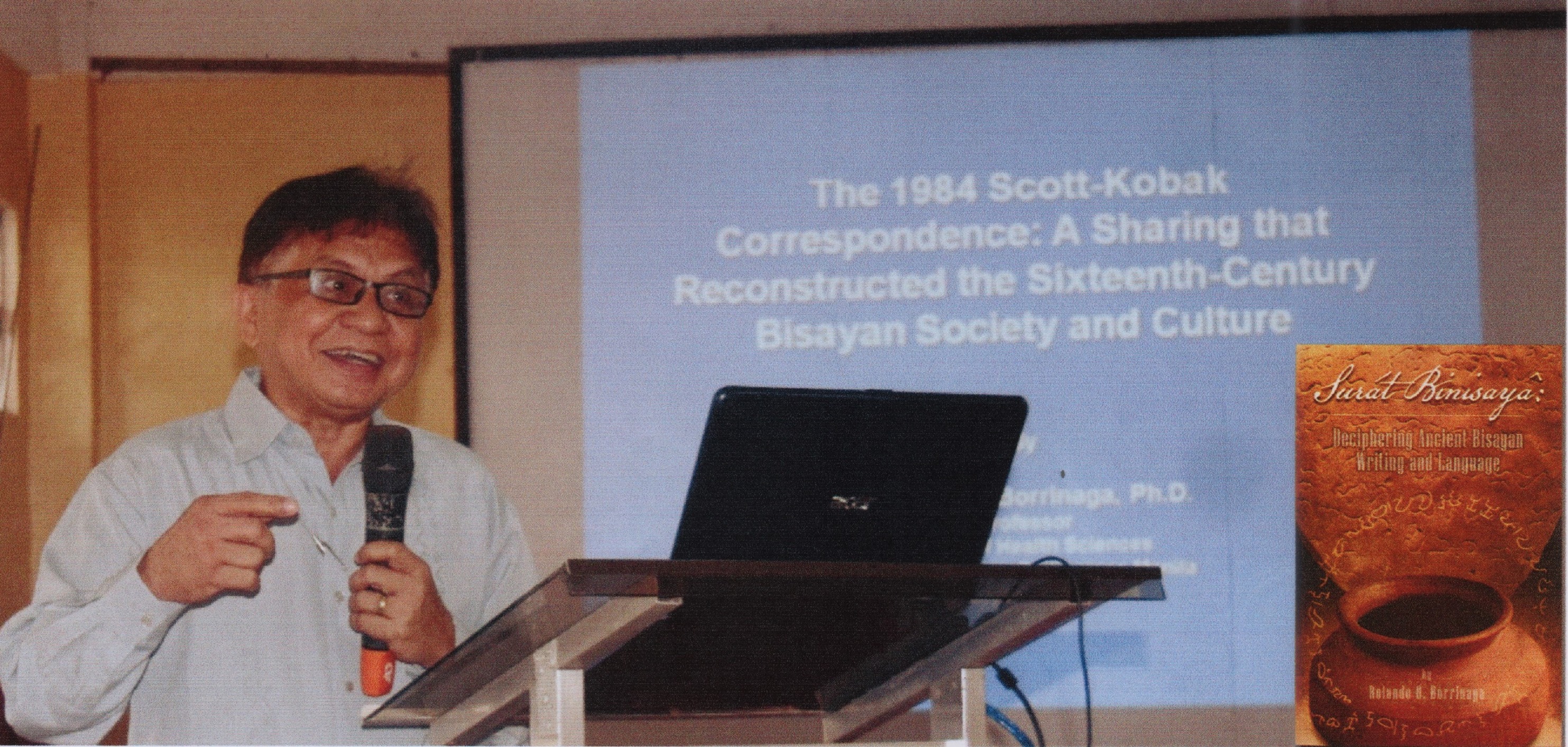

(The Lecture on Baybayin Writing was conducted by UP Prof. Rolando Borrinaga at the Audio-visual Room of Christ the King College in Calbayog City, Samar, on November 9, 2017. The lecture with Baybayin Writing exercises was organized by CKC Cantius Kobak Research Center in connection to the 50 Years Celebration of the founding of CKC Samar Archaeological Museum.)

ABSTRACT

In 2008 the author cracked a 50-year-old puzzle, the ancient Philippine script (baybayin) written around the mouth of the Calatagan Pot, a National Cultural Treasure displayed at the National Museum of Anthropology in Manila. The method he developed later proved useful in deciphering the baybayin writings on two Monreal Stones, discovered in Masbate Province in 2011. In October 2015, he likewise deciphered the purported ancient writing on the Intramuros Pot Shard, which was likened to the Calatagan Pot upon its discovery in 2008. In November 2015, he deciphered the baybayin writing embossed on a tiny celadon pot discovered in Limasawa, Southern Leyte. The transcription presented the outline of a bakalag, the ancient Bisayan human sacrifice ritual. This paper presents key findings and highlights of the author’s efforts at deciphering ancient Bisayan writing on recently-discovered artifacts in the country.

KEYWORDS: baybayin (ancient Philippine script), Calatagan Pot, Monreal Stones, Intramuros Pot Shard, Limasawa Pot, National Museum of Anthropology (Manila)

INTRODUCTION

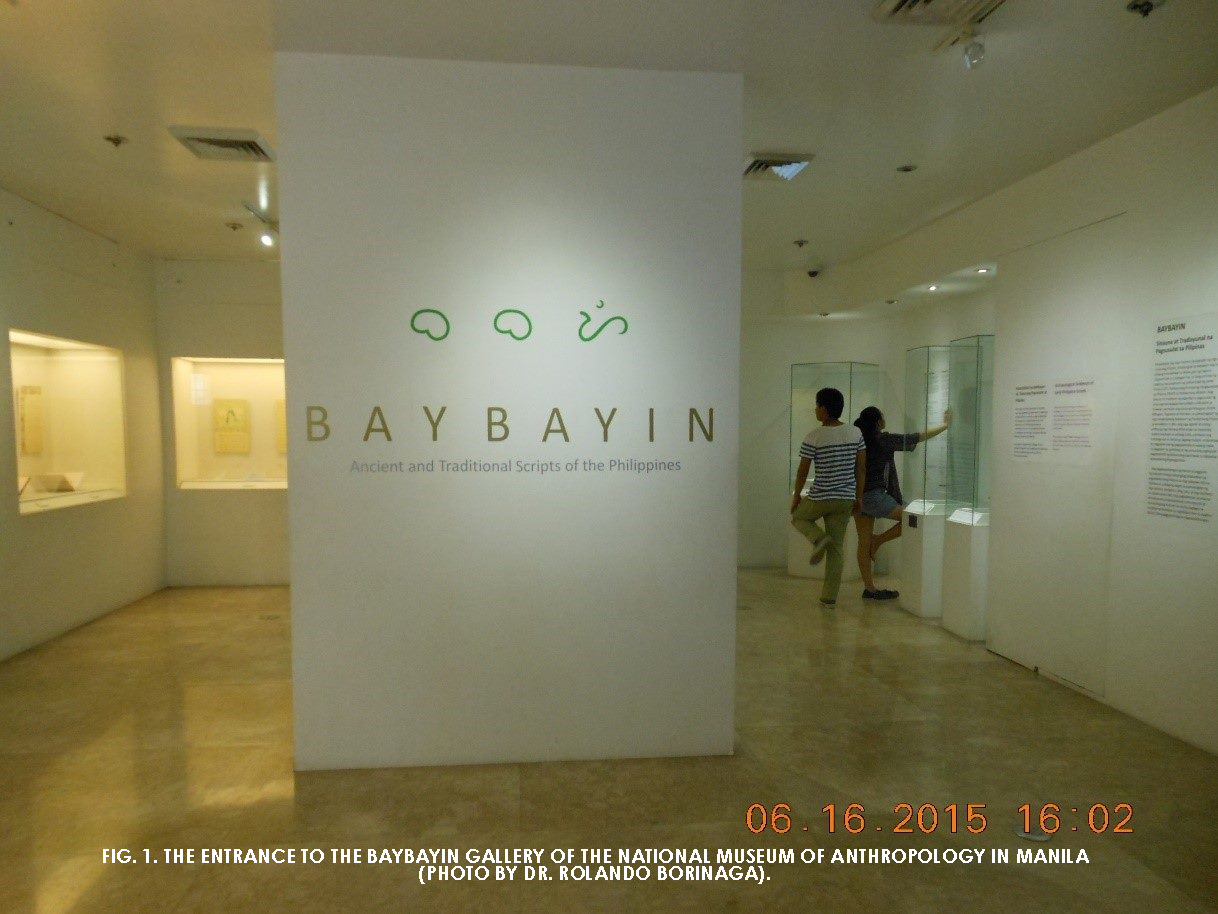

This paper presents the author’s efforts at deciphering ancient Bisayan writing on recently-discovered artifacts in the Philippines. Four of these artifacts – the Calatagan Pot, two Monreal Stones (the Monreal Round Stone and Monreal Trapezoidal Stone), and the Intramuros Pot Shard - are now on permanent display at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology in Manila. The fifth (the Limasawa Pot) is being recommended for acquisition by the National Museum from its private owner. Four artifacts with writings in baybayin, the ancient Philippine script, have been the subject of three full papers presented in different national conferences, two of which have been published in a journal (Borrinaga 2011; 2016a; 2016b). The writing on one artifact, which was purported to be baybayin but not quite, is presented and discussed here for the first time.

The author will not go into the details of the decoding and decipherment processes of the writings on these artifacts, because these are already discussed in the respective full papers. Instead, he will mainly present the transcriptions, translations, and summary analysis of the texts from the ancient writings and draw out some patterns and conclusion that can be derived from them.

ABSTRACT

In 2008 the author cracked a 50-year-old puzzle, the ancient Philippine script (baybayin) written around the mouth of the Calatagan Pot, a National Cultural Treasure displayed at the National Museum of Anthropology in Manila. The method he developed later proved useful in deciphering the baybayin writings on two Monreal Stones, discovered in Masbate Province in 2011. In October 2015, he likewise deciphered the purported ancient writing on the Intramuros Pot Shard, which was likened to the Calatagan Pot upon its discovery in 2008. In November 2015, he deciphered the baybayin writing embossed on a tiny celadon pot discovered in Limasawa, Southern Leyte. The transcription presented the outline of a bakalag, the ancient Bisayan human sacrifice ritual. This paper presents key findings and highlights of the author’s efforts at deciphering ancient Bisayan writing on recently-discovered artifacts in the country.

KEYWORDS: baybayin (ancient Philippine script), Calatagan Pot, Monreal Stones, Intramuros Pot Shard, Limasawa Pot, National Museum of Anthropology (Manila)

INTRODUCTION

This paper presents the author’s efforts at deciphering ancient Bisayan writing on recently-discovered artifacts in the Philippines. Four of these artifacts – the Calatagan Pot, two Monreal Stones (the Monreal Round Stone and Monreal Trapezoidal Stone), and the Intramuros Pot Shard - are now on permanent display at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology in Manila. The fifth (the Limasawa Pot) is being recommended for acquisition by the National Museum from its private owner. Four artifacts with writings in baybayin, the ancient Philippine script, have been the subject of three full papers presented in different national conferences, two of which have been published in a journal (Borrinaga 2011; 2016a; 2016b). The writing on one artifact, which was purported to be baybayin but not quite, is presented and discussed here for the first time.

The author will not go into the details of the decoding and decipherment processes of the writings on these artifacts, because these are already discussed in the respective full papers. Instead, he will mainly present the transcriptions, translations, and summary analysis of the texts from the ancient writings and draw out some patterns and conclusion that can be derived from them.

1. THE CALATAGAN POT

The Calatagan Pot is the iconic Philippine artifact with baybayin writing around its shoulder. It was declared a National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines on 14 June 2010 (bronze marker on its glass display case).

As its name suggests, the pot was discovered by local diggers at an archaeological excavation site in Calatagan, Batangas in 1958. This artifact was later acquired by the Anthropological Foundation of the Philippines, which in turn donated it in 1961 to the National Museum, where it is presently displayed (Ilagan 2008, 1-2).

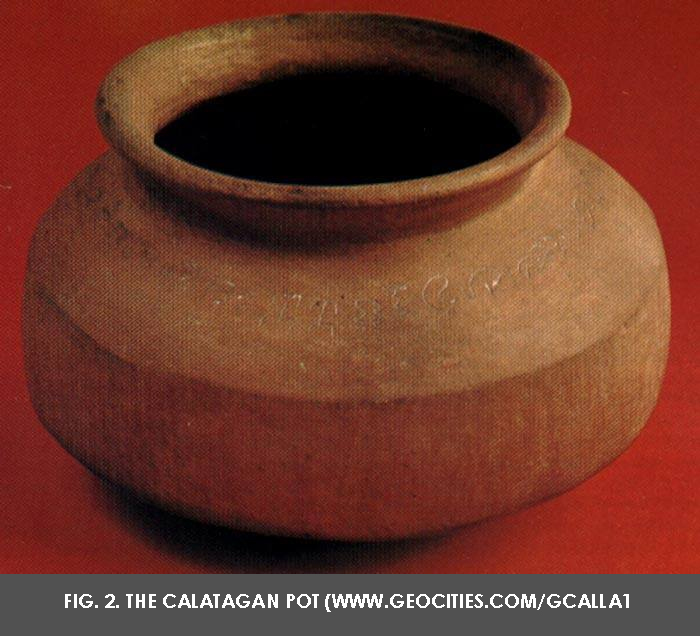

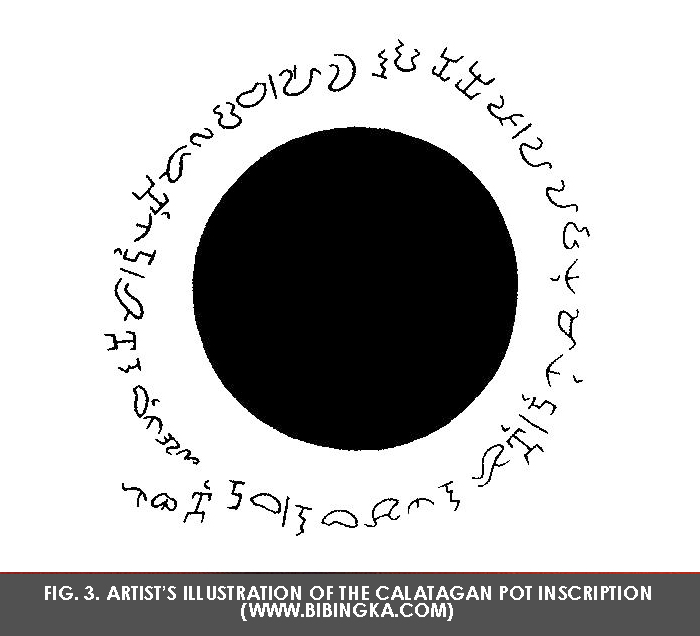

The Calatagan Pot (see Fig. 2) measures 12 cms. high and 20.2 cms. at its widest and weighs 872 grams. It is considered one of the country’s most valuable cultural and anthropological artifacts. The first pot with inscription to be dug out archeologically in the country, it has been dated between the 14th and 16th centuries (Ibid). Fig. 3 provides an artist’s illustration of the full inscription around the shoulder of the pot (www.bibingka.com).

The Calatagan Pot is the iconic Philippine artifact with baybayin writing around its shoulder. It was declared a National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines on 14 June 2010 (bronze marker on its glass display case).

As its name suggests, the pot was discovered by local diggers at an archaeological excavation site in Calatagan, Batangas in 1958. This artifact was later acquired by the Anthropological Foundation of the Philippines, which in turn donated it in 1961 to the National Museum, where it is presently displayed (Ilagan 2008, 1-2).

The Calatagan Pot (see Fig. 2) measures 12 cms. high and 20.2 cms. at its widest and weighs 872 grams. It is considered one of the country’s most valuable cultural and anthropological artifacts. The first pot with inscription to be dug out archeologically in the country, it has been dated between the 14th and 16th centuries (Ibid). Fig. 3 provides an artist’s illustration of the full inscription around the shoulder of the pot (www.bibingka.com).

Given these circumstances, the phrase “recently-discovered” does not apply to the Calatagan Pot itself. Instead, the phrase is made to apply to the recent final unravelling of its mysterious inscription, which had remained an enigma for 50 years from its discovery in 1958 until 2008. In the latter year, the author made his own transcription, translation, analysis and conclusion that the text on the pot was written in the old Bisayan language. A feature article with the preliminary findings was published in the Philippine Daily Inquirer on 23 May 2009 (Borrinaga 2009a, A16).

Not long afterwards, the author wrote a full academic paper about his findings on the Calatagan Pot inscription, which he presented at a national conference and had been published in a journal (Borrinaga 2011). At present, his decipherment and analysis has been adopted and given credence by the National Museum of the Philippines, both in a poster and in the narrative of a running video presentation at its Baybayin Gallery.

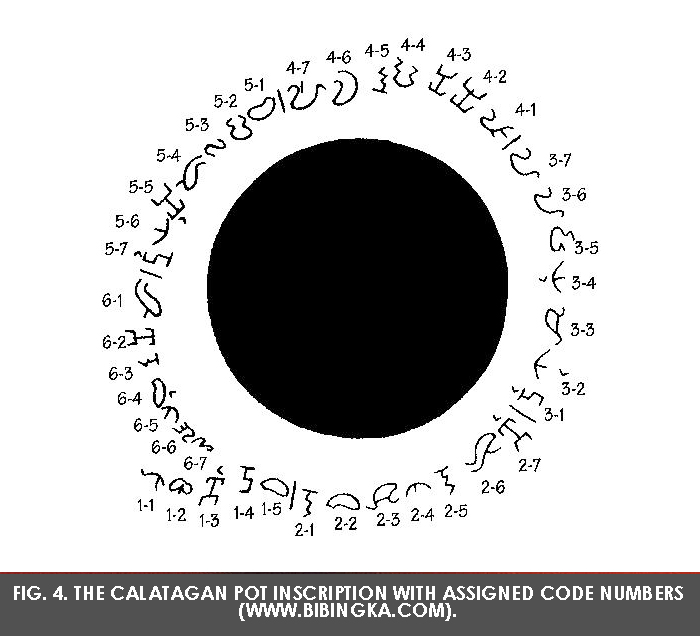

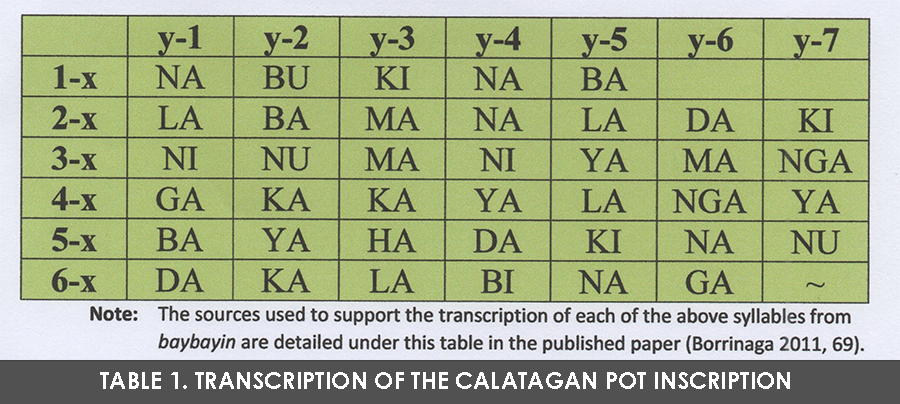

DECIPHERMENT TEMPLATE. In the process of deciphering the baybayin characters on the Calatagan Pot, the author used the numbered codes provided in Fig. 4, which had also been used for the common template to represent previous attempts to decipher the inscription on the pot. Table 1 provides my transcription of each of the represented characters. Letter “x” represents the first number in each code; letter “y” represents the second number in the code.

Not long afterwards, the author wrote a full academic paper about his findings on the Calatagan Pot inscription, which he presented at a national conference and had been published in a journal (Borrinaga 2011). At present, his decipherment and analysis has been adopted and given credence by the National Museum of the Philippines, both in a poster and in the narrative of a running video presentation at its Baybayin Gallery.

DECIPHERMENT TEMPLATE. In the process of deciphering the baybayin characters on the Calatagan Pot, the author used the numbered codes provided in Fig. 4, which had also been used for the common template to represent previous attempts to decipher the inscription on the pot. Table 1 provides my transcription of each of the represented characters. Letter “x” represents the first number in each code; letter “y” represents the second number in the code.

DECIPHERED BISAYAN WORDS: The deciphered Bisayan words from the transcription, some provided with end-consonants and one with a repeated syllable, and with the English translation of key words, are as follows:

NA-BU-KI-(KI) NA BA

Open, Already, Is it?

LA-BA MA NA LA DA-KI(T)

Gain, That’s It, Already, Nevertheless, Dãkit Tree

NI-NU MA NIYA MA-N(G)GA

Mistook, That’s It, By Him/Her, Mango Tree

GA-KA(T)-KA(T) YA LA NGA-YA(N)

Crossed due to fear, He/She, Only, Is That So?

BA-YA HA DA-KI(T) NA NU

Leave, From, Dakit Tree, Already, Will You?

DA KA-LA(G) BI-NA-GA(T) ~

Shame/Intimidate/Bring Back, Soul, Encountered

The full paper included a glossary of 26 possible Bisayan words that can be inferred from the deciphered inscription on the Calatagan Pot.

TRANSLATION AND CONTEXT: The Bisayan narrative of the transcribed text from the Calatagan Pot Inscription, with its corresponding English translation, provides an actor’s guide for a live ritual drama as follows:

Nabukîkî na ba?

Labâ mâ na lâ, dãkit,

Ninû mâ niya mangga,

Gakatkat ‘ya lâ ngay-an,

Bayâ ha dãkit na, nu?

Dã kalág binagat. ~

Is it open already? [the gateway to the spirit underworld]

Take it as a gain now, nevertheless, dãkit tree,

That he/she [strayed soul] mistook you for a mango tree,

[He/She] just crossed [to your domain] out of fear alone, is that so?

Leave the dãkit tree now, will you?

Shame/Intimidate/Bring [back] the soul that you [were told to] encounter.

FUNCTION OF THE POT: It appears that the Calatagan artifact was a ritual pot particularly used as native incense burner or oil or water container for the expensive and elaborate pag-ulî (return) ceremony of the pre-Hispanic Filipinos (Borrinaga 2011a, 71). This was presumably performed in front of a dãkit (balete to the Tagalogs), a tree held sacred by the natives, to retrieve a soul believed to have just crossed over to the other realm, and to return this to its moribund earthly body.

The inscription outlines a three-stage monologue, presumably elaborated with body movements and dancing by a babaylan (native priestess) in a trance during the ritual. It is alternately addressed to the humalagar or ancestor-spirit that the babaylan had commissioned for the soul-retrieval operation (lines 1, 5 and 6) on the one hand and, on the other, to the spirit underworld represented by the dãkit tree (lines 2, 3, and 4).

The same ritual pot was probably used also for ceremonies to retrieve victims of bugkut, disappeared persons believed to have been abducted by fairies who dwell in the dãkit (Ibid., 72).

THE MONREAL STONES: On 20 June 2011, a press conference held at the University of the Philippines Diliman in Quezon City formally introduced to the Filipino nation and the academic community two stone tablets carved with ancient baybayin characters. Initially called the “Rizal Stones,” these artifacts were found inside the compound of Rizal Elementary School, about seven km. south of the población of Monreal town, on Ticao Island in Masbate Province (personal communications with Dr. Francisco Datar and Dr. Ricardo Nolasco).

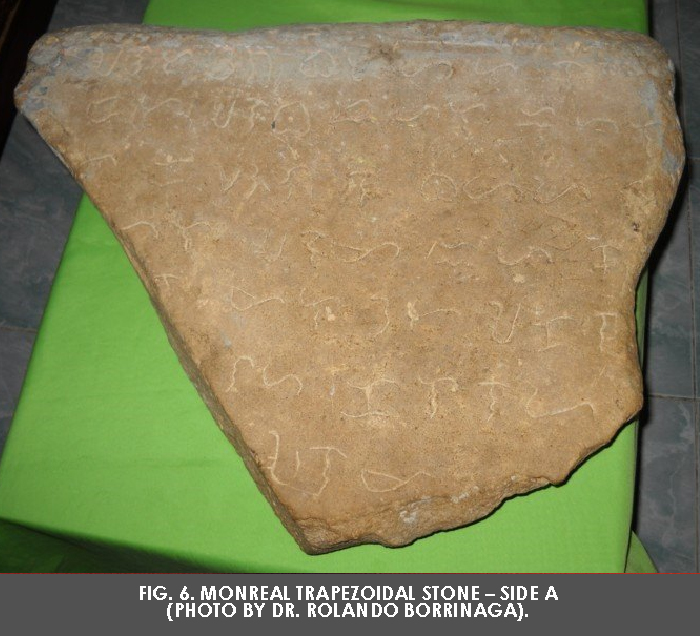

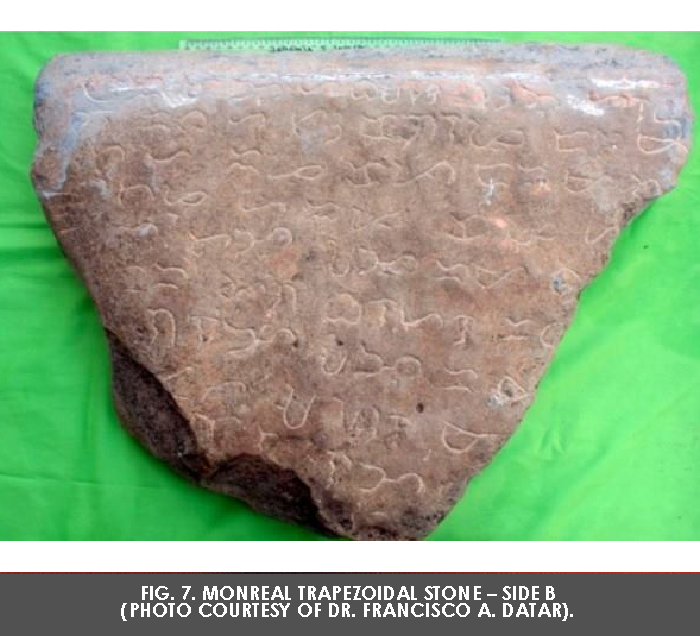

The bigger stone is roughly trapezoidal in shape, weighs 42 kg., measures about 57 cm. at its longest, 44 cm. at its widest, and is from 9 to 11 cm. thick. It has baybayin inscriptions on both sides, which means that the stone was designed to be viewed erect. Side A has 7 rows of writing with 54 characters; Side B has 10 rows of writing with 81 characters. The smaller stone has a round shape, 22 cm. long and 18 cm. wide, 6 cm. thick, and weighs 3.3 kg. It has 3 rows of writing with 17 characters carved on one side, and none on the underside. (The measurements were made by Dr. Francisco Datar.)

The two stones were among those gathered inside the Rizal Elementary School compound in the year 2000 by pupils who were asked to find flat stones to be used as stepping stones along the pathway to the Grade IV classroom of Mr. Lucas Espiloy, a newly transferred teacher. Since then, the bigger stone had been used to wipe off mud and dust from the shoes or slippers of pupils or teachers before entering the classroom. The smaller stone was kept in a safe place inside (Borrinaga 2016a, 187).

The existence of these artifacts first reached the attention of Dr. Francisco A. Datar, an anthropology professor at U.P. Diliman, in April 2011. He traveled to Ticao Island to view these stones for himself, and then he organized an all-U.P. team to study the baybayin writings on them based on the photographs he took. The discovery was eventually disclosed to the nation and the world (Ibid., 188).

As an invited member of the U.P. research team, the author was the first to fully decipher, transcribe, and translate the baybayin writings on the Monreal Stones, using essentially the same method and approach that he had developed to decipher the Calatagan Pot inscription in 2008. It helped that the writings on the two stones are also in the Bisayan language. He presented his findings in a paper read at the 1st Philippine Conference on the “Baybayin” Stones of Ticao, Masbate, held in Monreal, Masbate Province on 5-6 August 2011 (Ibid.).

The Monreal Stones are now center-piece display items at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology in Manila, which was formally opened to the public on 20 February 2013 (National Museum of the Philippines, Facebook account).

2. THE MONREAL ROUND STONE

NA-BU-KI-(KI) NA BA

Open, Already, Is it?

LA-BA MA NA LA DA-KI(T)

Gain, That’s It, Already, Nevertheless, Dãkit Tree

NI-NU MA NIYA MA-N(G)GA

Mistook, That’s It, By Him/Her, Mango Tree

GA-KA(T)-KA(T) YA LA NGA-YA(N)

Crossed due to fear, He/She, Only, Is That So?

BA-YA HA DA-KI(T) NA NU

Leave, From, Dakit Tree, Already, Will You?

DA KA-LA(G) BI-NA-GA(T) ~

Shame/Intimidate/Bring Back, Soul, Encountered

The full paper included a glossary of 26 possible Bisayan words that can be inferred from the deciphered inscription on the Calatagan Pot.

TRANSLATION AND CONTEXT: The Bisayan narrative of the transcribed text from the Calatagan Pot Inscription, with its corresponding English translation, provides an actor’s guide for a live ritual drama as follows:

Nabukîkî na ba?

Labâ mâ na lâ, dãkit,

Ninû mâ niya mangga,

Gakatkat ‘ya lâ ngay-an,

Bayâ ha dãkit na, nu?

Dã kalág binagat. ~

Is it open already? [the gateway to the spirit underworld]

Take it as a gain now, nevertheless, dãkit tree,

That he/she [strayed soul] mistook you for a mango tree,

[He/She] just crossed [to your domain] out of fear alone, is that so?

Leave the dãkit tree now, will you?

Shame/Intimidate/Bring [back] the soul that you [were told to] encounter.

FUNCTION OF THE POT: It appears that the Calatagan artifact was a ritual pot particularly used as native incense burner or oil or water container for the expensive and elaborate pag-ulî (return) ceremony of the pre-Hispanic Filipinos (Borrinaga 2011a, 71). This was presumably performed in front of a dãkit (balete to the Tagalogs), a tree held sacred by the natives, to retrieve a soul believed to have just crossed over to the other realm, and to return this to its moribund earthly body.

The inscription outlines a three-stage monologue, presumably elaborated with body movements and dancing by a babaylan (native priestess) in a trance during the ritual. It is alternately addressed to the humalagar or ancestor-spirit that the babaylan had commissioned for the soul-retrieval operation (lines 1, 5 and 6) on the one hand and, on the other, to the spirit underworld represented by the dãkit tree (lines 2, 3, and 4).

The same ritual pot was probably used also for ceremonies to retrieve victims of bugkut, disappeared persons believed to have been abducted by fairies who dwell in the dãkit (Ibid., 72).

THE MONREAL STONES: On 20 June 2011, a press conference held at the University of the Philippines Diliman in Quezon City formally introduced to the Filipino nation and the academic community two stone tablets carved with ancient baybayin characters. Initially called the “Rizal Stones,” these artifacts were found inside the compound of Rizal Elementary School, about seven km. south of the población of Monreal town, on Ticao Island in Masbate Province (personal communications with Dr. Francisco Datar and Dr. Ricardo Nolasco).

The bigger stone is roughly trapezoidal in shape, weighs 42 kg., measures about 57 cm. at its longest, 44 cm. at its widest, and is from 9 to 11 cm. thick. It has baybayin inscriptions on both sides, which means that the stone was designed to be viewed erect. Side A has 7 rows of writing with 54 characters; Side B has 10 rows of writing with 81 characters. The smaller stone has a round shape, 22 cm. long and 18 cm. wide, 6 cm. thick, and weighs 3.3 kg. It has 3 rows of writing with 17 characters carved on one side, and none on the underside. (The measurements were made by Dr. Francisco Datar.)

The two stones were among those gathered inside the Rizal Elementary School compound in the year 2000 by pupils who were asked to find flat stones to be used as stepping stones along the pathway to the Grade IV classroom of Mr. Lucas Espiloy, a newly transferred teacher. Since then, the bigger stone had been used to wipe off mud and dust from the shoes or slippers of pupils or teachers before entering the classroom. The smaller stone was kept in a safe place inside (Borrinaga 2016a, 187).

The existence of these artifacts first reached the attention of Dr. Francisco A. Datar, an anthropology professor at U.P. Diliman, in April 2011. He traveled to Ticao Island to view these stones for himself, and then he organized an all-U.P. team to study the baybayin writings on them based on the photographs he took. The discovery was eventually disclosed to the nation and the world (Ibid., 188).

As an invited member of the U.P. research team, the author was the first to fully decipher, transcribe, and translate the baybayin writings on the Monreal Stones, using essentially the same method and approach that he had developed to decipher the Calatagan Pot inscription in 2008. It helped that the writings on the two stones are also in the Bisayan language. He presented his findings in a paper read at the 1st Philippine Conference on the “Baybayin” Stones of Ticao, Masbate, held in Monreal, Masbate Province on 5-6 August 2011 (Ibid.).

The Monreal Stones are now center-piece display items at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology in Manila, which was formally opened to the public on 20 February 2013 (National Museum of the Philippines, Facebook account).

2. THE MONREAL ROUND STONE

Transcription of the Baybayin Characters:

Line 1: KA – HA – NGA – NA – NI

Line 2: NA – PA – LA – U – DA – NA

Line 3: NA – KA – TA – A – NA - /

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Kahang na ni [?]

Napala[w]ud na [?]

Nakataa[n] na /

English Translation:

Is this already the boundary (kahang)?

Has [it] gone to deep sea (lawud)?

This has been allowed (nakataan) to be set here already [end marker].

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Artifact

The Monreal Round Stone appears to have functioned as stone sinker at the end of a heavy-duty fishing net centuries ago, presumably the one called panamaw, which was used to catch large species of fish. Jesuit Fr. Francisco Alcina in his 1668 manuscripts (Ch. 16, Bk. 2, Part I) described that these nets were set in place in the sea; they were likewise used on land to catch wild hogs and other animals. At sea, they ordinarily caught duyungs (sea cows) and species of manta ray such as saranga, punsuan, dahunan, bituunun, and banugun (Ibid.).

This artifact could not have served as sinker for the ordinary gill net, called pukut, which was allowed to drift at sea in many instances and just required smaller stone sinkers to keep the bottom part of the net vertically under water.

The specific areas of the sea for setting the panamaw net that would have been anchored by the Monreal Round Stone (along with several other similar-sized but plain stone sinkers) seemed to have been pre-established by native rituals negotiated with the spirits of the sea (Arens 1971, 42-46). The baybayin characters written on the stone seemed like a prepared apology (to the literate spirits) in the event that the net had been unwittingly set outside the negotiated inshore-offshore boundary or had been dragged to outer boundaries by the heavy volume of catch.

3. THE MONREAL TRAPEZOIDAL STONE

3.1 Monreal Trapezoidal Stone – Side A

Line 1: KA – HA – NGA – NA – NI

Line 2: NA – PA – LA – U – DA – NA

Line 3: NA – KA – TA – A – NA - /

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Kahang na ni [?]

Napala[w]ud na [?]

Nakataa[n] na /

English Translation:

Is this already the boundary (kahang)?

Has [it] gone to deep sea (lawud)?

This has been allowed (nakataan) to be set here already [end marker].

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Artifact

The Monreal Round Stone appears to have functioned as stone sinker at the end of a heavy-duty fishing net centuries ago, presumably the one called panamaw, which was used to catch large species of fish. Jesuit Fr. Francisco Alcina in his 1668 manuscripts (Ch. 16, Bk. 2, Part I) described that these nets were set in place in the sea; they were likewise used on land to catch wild hogs and other animals. At sea, they ordinarily caught duyungs (sea cows) and species of manta ray such as saranga, punsuan, dahunan, bituunun, and banugun (Ibid.).

This artifact could not have served as sinker for the ordinary gill net, called pukut, which was allowed to drift at sea in many instances and just required smaller stone sinkers to keep the bottom part of the net vertically under water.

The specific areas of the sea for setting the panamaw net that would have been anchored by the Monreal Round Stone (along with several other similar-sized but plain stone sinkers) seemed to have been pre-established by native rituals negotiated with the spirits of the sea (Arens 1971, 42-46). The baybayin characters written on the stone seemed like a prepared apology (to the literate spirits) in the event that the net had been unwittingly set outside the negotiated inshore-offshore boundary or had been dragged to outer boundaries by the heavy volume of catch.

3. THE MONREAL TRAPEZOIDAL STONE

3.1 Monreal Trapezoidal Stone – Side A

Transcription of the Baybayin Characters:

Line 1: A – NA – TA – U – GA – BA – TA – HA – LA – NA

Line 2: DI – TA – A – NA – BA – I – HA – LA – I – HA – LA

Line 3: HA – KA – SA – GA – NA – BA – HA – YA – NA

Line 4: HA – TA – A – NA – NGA – I – HA – LA

Line 5: NA – NGA – LA – U – TA – A – KA – NA

Line 6: LA – HA – KA – LA – NA – MA

Line 7: A – NA – NGA

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Anata! Uga[k], bata! Hala na!

Ditaa[n] na ba? Ihala[d]! Ihala[d]!

Haka [sa] sagana bahaya[n] na.

Hataa[n] na nga ihala[d].

Nangala[w]u[d], taaka na

la ha kala[g] na ma-

angga.

English Translation:

Spread [it out]! Tease [the nature spirits], child! Come on now!

Have you put dita on it? Offer it! Offer it!

Fear of the roaring sea should mean reinforced nets and/or boats now.

Allow it to be offered [then].

Those who had gone to deep sea, get lost (taak) now

from the soul that

tends to beg your confidence [or: starts to …].

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Writing on Side A of the Stone:

Side A of the Monreal Trapezoidal Stone seemed to have originally functioned as a platform for ritual offerings in a native simbahan or place of worship, probably during pre-Spanish times. The baybayin characters on it contain an outline for a live ritual drama, perhaps complemented with expanded monologue presumably performed by a babaylan (native priestess or worship leader) and accompanied by patterned body movements or ritual dancing, both by the babaylan and the worshippers in attendance. The purpose of the ritual was to avert material and human loss from fishing or sailing in adverse sea conditions.

3.2. Monreal Trapezoidal Stone – Side B

Line 1: A – NA – TA – U – GA – BA – TA – HA – LA – NA

Line 2: DI – TA – A – NA – BA – I – HA – LA – I – HA – LA

Line 3: HA – KA – SA – GA – NA – BA – HA – YA – NA

Line 4: HA – TA – A – NA – NGA – I – HA – LA

Line 5: NA – NGA – LA – U – TA – A – KA – NA

Line 6: LA – HA – KA – LA – NA – MA

Line 7: A – NA – NGA

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Anata! Uga[k], bata! Hala na!

Ditaa[n] na ba? Ihala[d]! Ihala[d]!

Haka [sa] sagana bahaya[n] na.

Hataa[n] na nga ihala[d].

Nangala[w]u[d], taaka na

la ha kala[g] na ma-

angga.

English Translation:

Spread [it out]! Tease [the nature spirits], child! Come on now!

Have you put dita on it? Offer it! Offer it!

Fear of the roaring sea should mean reinforced nets and/or boats now.

Allow it to be offered [then].

Those who had gone to deep sea, get lost (taak) now

from the soul that

tends to beg your confidence [or: starts to …].

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Writing on Side A of the Stone:

Side A of the Monreal Trapezoidal Stone seemed to have originally functioned as a platform for ritual offerings in a native simbahan or place of worship, probably during pre-Spanish times. The baybayin characters on it contain an outline for a live ritual drama, perhaps complemented with expanded monologue presumably performed by a babaylan (native priestess or worship leader) and accompanied by patterned body movements or ritual dancing, both by the babaylan and the worshippers in attendance. The purpose of the ritual was to avert material and human loss from fishing or sailing in adverse sea conditions.

3.2. Monreal Trapezoidal Stone – Side B

Transcription of the Baybayin Characters:

Line 1: DA – I – MA – NGA – HA – BA – A – SA – SI – NGU – TA – NA – DA

Line 2: NA – KA – BA – HA – TA – U – KU – GA – NA – RA – DA – I – MA

Line 3: TA – HA – I – RA – KA – PA – DA – I – MA – GA

Line 4: TA – RU – HA – I – RA – KA – RA – HA

Line 5: HA – TA – NGA – A – NGA – I – MA – BA

Line 6: KA – I – PA – GA – BA – LA – HA – NA – I – BA

Line 7: GA – NA – NGA – A – NGA – I - NGA

Line 8: DA – TA – A – SA – NA – MA

Line 9: DA – GA – NA – NGU – TA

Line 10: NA

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Day, manga hab[w]a sa singu[t] ta [a]na da!

Nakabaha[g] ta[w]u[n] ko. Gana ra, Day. Ma-

taha. Ira ka pa, Day. Maga-

taro ha ira karaha.

Hata[g] nga anga imaba

kay pagaba la ha naiba.

Gana nga anga inga-

da ta. Asa na ma[n]

daga nanguta -

na?

English Translation:

Woman, we would be drained of perspiration with that, really!

I am in g-string, what a pity! Just a desire, Woman. Full of

respect. You are still theirs [her masters], Woman. Processing

beeswax in their steel pans.

Gift of affection should be humbled

because it just comes closer to many others.

[The] affection that is desired we put

in there. Where is the

lady who asked the question?

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Writing on Side B of the Stone:

The baybayin writing on Side B of the Monreal Trapezoidal Stone, while still barely deciphered, became the focus of controversy after pictures of the two artifacts were presented by the University of the Philippines research team to the media at the U.P. Diliman press conference on 20 June 2011 and then broadcast the next day by GMA-7, a national TV station (Lapeña and Severino 2011; Dacanay 2011).

The most serious accusation was that this stone artifact is probably a “modern-day hoax” (Dacanay 2011). The hoax theory was premised on the observation of some baybayin experts, upon studying the released photographs, that the writing “just looks too modern” (Ibid.) and that the letters’ shapes [on Side B] “resemble a typeface that was developed for a Spanish printing press in the early 1600s” (Lapeña and Severino 2011).

The initial critics’ concerns were verbalized by Paul Morrow, a baybayin expert, as follows: “It could have been an innocent exercise of a 20th century baybayin enthusiast who lacked some basic knowledge about the script and had no intention deceiving anybody... Or it could be a hoax” (Morrow 2011).

In the light of the international debate that has erupted over the writing on Side B of this artifact, the narrative of its fully deciphered baybayin text can actually speak for itself. It presents a humorous tale of a botched attempt by a man to woo a woman, revolving around a Bisayan proverb that translates as “Gift of affection should be humbled / because it just comes closer to many others.”

Transcription of the Baybayin Characters

Line 1: DA – I – MA – NGA – HA – BA – A – SA – SI – NGU – TA – NA – DA

Line 2: NA – KA – BA – HA – TA – U – KU – GA – NA – RA – DA – I – MA

Line 3: TA – HA – I – RA – KA – PA – DA – I – MA – GA

Line 4: TA – RU – HA – I – RA – KA – RA – HA

Line 5: HA – TA – NGA – A – NGA – I – MA – BA

Line 6: KA – I – PA – GA – BA – LA – HA – NA – I – BA

Line 7: GA – NA – NGA – A – NGA – I - NGA

Line 8: DA – TA – A – SA – NA – MA

Line 9: DA – GA – NA – NGU – TA

Line 10: NA

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Day, manga hab[w]a sa singu[t] ta [a]na da!

Nakabaha[g] ta[w]u[n] ko. Gana ra, Day. Ma-

taha. Ira ka pa, Day. Maga-

taro ha ira karaha.

Hata[g] nga anga imaba

kay pagaba la ha naiba.

Gana nga anga inga-

da ta. Asa na ma[n]

daga nanguta -

na?

English Translation:

Woman, we would be drained of perspiration with that, really!

I am in g-string, what a pity! Just a desire, Woman. Full of

respect. You are still theirs [her masters], Woman. Processing

beeswax in their steel pans.

Gift of affection should be humbled

because it just comes closer to many others.

[The] affection that is desired we put

in there. Where is the

lady who asked the ques-

tion?

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Writing on Side B of the Stone:

The baybayin writing on Side B of the Monreal Trapezoidal Stone, while still barely deciphered, became the focus of controversy after pictures of the two artifacts were presented by the University of the Philippines research team to the media at the U.P. Diliman press conference on 20 June 2011 and then broadcast the next day by GMA-7, a national TV station (Lapeña and Severino 2011; Dacanay 2011).

The most serious accusation was that this stone artifact is probably a “modern-day hoax” (Dacanay 2011). The hoax theory was premised on the observation of some baybayin experts, upon studying the released photographs, that the writing “just looks too modern” (Ibid.) and that the letters’ shapes [on Side B] “resemble a typeface that was developed for a Spanish printing press in the early 1600s” (Lapeña and Severino 2011).

The initial critics’ concerns were verbalized by Paul Morrow, a baybayin expert, as follows: “It could have been an innocent exercise of a 20th century baybayin enthusiast who lacked some basic knowledge about the script and had no intention deceiving anybody... Or it could be a hoax” (Morrow 2011).

In the light of the international debate that has erupted over the writing on Side B of this artifact, the narrative of its fully deciphered baybayin text can actually speak for itself. It presents a humorous tale of a botched attempt by a man to woo a woman, revolving around a Bisayan proverb that translates as “Gift of affection should be humbled / because it just comes closer to many others.”

4. THE INTRAMUROS POT SHARD

The author’s original motivation to undertake deeper study of baybayin, the ancient Philippine syllabic writing, was triggered quite accidentally early morning on 18 November 2008. While browsing the Internet for materials on the old Philippine scripts, he came across an item dated 22 September 2008, which reported the discovery of a pot shard with alleged ancient inscription around its shoulder, dug up at an archaeological site in Intramuros, Manila (Philippine News.net, 2008).

A few weeks earlier, on 24 October 2008, he had presented a paper on the 1984 correspondence between the late William Henry Scott and the late Fr. Cantius K. Kobak, OFM, two foremost scholars on the sixteenth-century society and culture of the Bisayas, at the 29th National Conference of the Philippine National Historical Society in Banaue, Ifugao (Borrinaga 2009b, 205-225). Since the paper included as attachments a set of three ancient Bisayan syllabic writing compiled by Father Kobak and seventeenth-century Tagalog scripts summarized by Scott, he thought he could use these documents as guides in deciphering the inscription on the Calatagan Pot, which he first read about in a column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer in 2007 (Ocampo 2007).

He searched the Internet for an illustration of this inscription and found and downloaded one (Fig. 3) from a blogspot item that cited its source as https://www.bibingka.com (Santos 1996). He then started the trial-and-error deciphering process using the Kobak and Scott materials as guides and made it half-way during the day. The rest is history, so to speak (Borrinaga 2011a).

Line 1: DA – I – MA – NGA – HA – BA – A – SA – SI – NGU – TA – NA – DA

Line 2: NA – KA – BA – HA – TA – U – KU – GA – NA – RA – DA – I – MA

Line 3: TA – HA – I – RA – KA – PA – DA – I – MA – GA

Line 4: TA – RU – HA – I – RA – KA – RA – HA

Line 5: HA – TA – NGA – A – NGA – I – MA – BA

Line 6: KA – I – PA – GA – BA – LA – HA – NA – I – BA

Line 7: GA – NA – NGA – A – NGA – I - NGA

Line 8: DA – TA – A – SA – NA – MA

Line 9: DA – GA – NA – NGU – TA

Line 10: NA

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Day, manga hab[w]a sa singu[t] ta [a]na da!

Nakabaha[g] ta[w]u[n] ko. Gana ra, Day. Ma-

taha. Ira ka pa, Day. Maga-

taro ha ira karaha.

Hata[g] nga anga imaba

kay pagaba la ha naiba.

Gana nga anga inga-

da ta. Asa na ma[n]

daga nanguta -

na?

English Translation:

Woman, we would be drained of perspiration with that, really!

I am in g-string, what a pity! Just a desire, Woman. Full of

respect. You are still theirs [her masters], Woman. Processing

beeswax in their steel pans.

Gift of affection should be humbled

because it just comes closer to many others.

[The] affection that is desired we put

in there. Where is the

lady who asked the question?

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Writing on Side B of the Stone:

The baybayin writing on Side B of the Monreal Trapezoidal Stone, while still barely deciphered, became the focus of controversy after pictures of the two artifacts were presented by the University of the Philippines research team to the media at the U.P. Diliman press conference on 20 June 2011 and then broadcast the next day by GMA-7, a national TV station (Lapeña and Severino 2011; Dacanay 2011).

The most serious accusation was that this stone artifact is probably a “modern-day hoax” (Dacanay 2011). The hoax theory was premised on the observation of some baybayin experts, upon studying the released photographs, that the writing “just looks too modern” (Ibid.) and that the letters’ shapes [on Side B] “resemble a typeface that was developed for a Spanish printing press in the early 1600s” (Lapeña and Severino 2011).

The initial critics’ concerns were verbalized by Paul Morrow, a baybayin expert, as follows: “It could have been an innocent exercise of a 20th century baybayin enthusiast who lacked some basic knowledge about the script and had no intention deceiving anybody... Or it could be a hoax” (Morrow 2011).

In the light of the international debate that has erupted over the writing on Side B of this artifact, the narrative of its fully deciphered baybayin text can actually speak for itself. It presents a humorous tale of a botched attempt by a man to woo a woman, revolving around a Bisayan proverb that translates as “Gift of affection should be humbled / because it just comes closer to many others.”

Transcription of the Baybayin Characters

Line 1: DA – I – MA – NGA – HA – BA – A – SA – SI – NGU – TA – NA – DA

Line 2: NA – KA – BA – HA – TA – U – KU – GA – NA – RA – DA – I – MA

Line 3: TA – HA – I – RA – KA – PA – DA – I – MA – GA

Line 4: TA – RU – HA – I – RA – KA – RA – HA

Line 5: HA – TA – NGA – A – NGA – I – MA – BA

Line 6: KA – I – PA – GA – BA – LA – HA – NA – I – BA

Line 7: GA – NA – NGA – A – NGA – I - NGA

Line 8: DA – TA – A – SA – NA – MA

Line 9: DA – GA – NA – NGU – TA

Line 10: NA

Deciphered Bisayan Words:

Day, manga hab[w]a sa singu[t] ta [a]na da!

Nakabaha[g] ta[w]u[n] ko. Gana ra, Day. Ma-

taha. Ira ka pa, Day. Maga-

taro ha ira karaha.

Hata[g] nga anga imaba

kay pagaba la ha naiba.

Gana nga anga inga-

da ta. Asa na ma[n]

daga nanguta -

na?

English Translation:

Woman, we would be drained of perspiration with that, really!

I am in g-string, what a pity! Just a desire, Woman. Full of

respect. You are still theirs [her masters], Woman. Processing

beeswax in their steel pans.

Gift of affection should be humbled

because it just comes closer to many others.

[The] affection that is desired we put

in there. Where is the

lady who asked the ques-

tion?

Note on the Possible Cultural Context of the Writing on Side B of the Stone:

The baybayin writing on Side B of the Monreal Trapezoidal Stone, while still barely deciphered, became the focus of controversy after pictures of the two artifacts were presented by the University of the Philippines research team to the media at the U.P. Diliman press conference on 20 June 2011 and then broadcast the next day by GMA-7, a national TV station (Lapeña and Severino 2011; Dacanay 2011).

The most serious accusation was that this stone artifact is probably a “modern-day hoax” (Dacanay 2011). The hoax theory was premised on the observation of some baybayin experts, upon studying the released photographs, that the writing “just looks too modern” (Ibid.) and that the letters’ shapes [on Side B] “resemble a typeface that was developed for a Spanish printing press in the early 1600s” (Lapeña and Severino 2011).

The initial critics’ concerns were verbalized by Paul Morrow, a baybayin expert, as follows: “It could have been an innocent exercise of a 20th century baybayin enthusiast who lacked some basic knowledge about the script and had no intention deceiving anybody... Or it could be a hoax” (Morrow 2011).

In the light of the international debate that has erupted over the writing on Side B of this artifact, the narrative of its fully deciphered baybayin text can actually speak for itself. It presents a humorous tale of a botched attempt by a man to woo a woman, revolving around a Bisayan proverb that translates as “Gift of affection should be humbled / because it just comes closer to many others.”

4. THE INTRAMUROS POT SHARD

The author’s original motivation to undertake deeper study of baybayin, the ancient Philippine syllabic writing, was triggered quite accidentally early morning on 18 November 2008. While browsing the Internet for materials on the old Philippine scripts, he came across an item dated 22 September 2008, which reported the discovery of a pot shard with alleged ancient inscription around its shoulder, dug up at an archaeological site in Intramuros, Manila (Philippine News.net, 2008).

A few weeks earlier, on 24 October 2008, he had presented a paper on the 1984 correspondence between the late William Henry Scott and the late Fr. Cantius K. Kobak, OFM, two foremost scholars on the sixteenth-century society and culture of the Bisayas, at the 29th National Conference of the Philippine National Historical Society in Banaue, Ifugao (Borrinaga 2009b, 205-225). Since the paper included as attachments a set of three ancient Bisayan syllabic writing compiled by Father Kobak and seventeenth-century Tagalog scripts summarized by Scott, he thought he could use these documents as guides in deciphering the inscription on the Calatagan Pot, which he first read about in a column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer in 2007 (Ocampo 2007).

He searched the Internet for an illustration of this inscription and found and downloaded one (Fig. 3) from a blogspot item that cited its source as https://www.bibingka.com (Santos 1996). He then started the trial-and-error deciphering process using the Kobak and Scott materials as guides and made it half-way during the day. The rest is history, so to speak (Borrinaga 2011a).

The author’s first sight of the Intramuros Pot Shard came in two photos published in a paper on the excavation at the Iglesia de San Ignacio site in Intramuros. It was considered “the most significant material found” in the site and the inscription on its shoulder was likened to that of the famous Calatagan Pot (Bautista 2010, 32-33).

Over the next few years, the author tried to ask from his National Museum contacts about any write-up on the shard, but he did not get much headway. Five years later, the shard was featured again in a published paper with updates on the Intramuros excavation, with matching clear photos (Bautista, et.al., 2015, 45-46). It described that “the ancient inscription was compared with Tagalog and Kapampangan scripts. It can be read tentatively as ‘Palaki’ and interpreted as A la ke (Alay Kay)” (Ibid., 45).

Finally, on 13 October 2015, the author found himself face-to-face with the Intramuros Pot Shard, encased in material that made it appear like a whole pot, which has been displayed at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology, next to the glass display case of the Calatagan Pot. The artifact was not yet there during his previous visit to the museum in June 2015.

ROMAN SCRIPT, NOT BAYBAYIN: The author decided to take the opportunity to look closely at the inscription on the Intramuros Pot Shard while biding time before billeting at a nearby hotel. Somewhat to his disappointment and contrary to his expectation all along, what he found was that the inscription on the shard was not baybayin but crudely-written lower-case Roman letters, which dates it to the Spanish era, and not as ancient as purported. What he deciphered were the following letters: [B]-a-g-t-i-n-g-ue-t-v-v-s-a-n.

The caption for the displayed artifact mentioned that: “Mrs. [EBG], a Cultural Heritage Advocate, compared the script with [T]agalog and [K]apampangan. A tentative deciphering revealed ‘pa-la-ki’ interpreted as ‘a-la-ke’ or ‘alay kay’.” However, the author could not seem to decipher the PA-LA-KI syllables from the script.

Hours later at the hotel, the author used computer blow-ups of his photos to look closer at the inscription on the shard. Only the upper curve of what appears to be capital letter B was visible on the left. He tried to coin words from the deciphered letters and came out with “bagting” or “bagtingi” (from “bagtingue”) and “utusan” or “tuusan.” “Bagting” or “bagtingi” in Bisayan language is to ring (i.e., a bell), but in Tagalog “bagting” is a cord or string for a musical instrument (on-line Tagalog-English translator). “Utusan” in Tagalog is a servant. In Binisayâ, the oldest dictionary (Sanchez 1711) has a word “Tous,” which is the synonym of “pa-id” (i.e., decorum or respect). “Tuusan” would thus mean to show or be shown decorum or respect.

Given the above decipherment and analysis, the author surmised that the Tagalog words “bagting” and “utusan” do not represent the inscription on this artifact with seemingly sacred function.

"RING IT (a bell), NOW RESPECT:" Thereafter, the author concluded that the inscription on the Intramuros Pot Shard is not baybayin but just crude cursive Roman script. The deciphered letters represent two undivided Bisayan words – (B)agtingue [bagtingi; “ring it”] and tvvsan [tuusan; archaic spelling, “show respect”]. In Binisayâ, “(B)agtingi[,] tuusan” literally means “Ring it (a bell), show respect” – which are acts related to the performance of a ritual.

We do not know the full set of acts outlined for the ritual inscribed on the Intramuros Pot Shard and what the ritual was for. The Roman script puts the inscription sometime in the Spanish colonial era, perhaps the 1600s. The artifact suggests the continuity of pot-using rituals that date back from the pre-Spanish era, as represented by the Calatagan Pot. But this time, a Christian bell might have been rung, and no longer the ancient agung or gong.

5. THE LIMASAWA POT

On 11 November 2015, the facilitators of the Cultural Mapping Workshop conducted in Limasawa, Southern Leyte, including the author, joined a local team in their field work to map and document tangible heritage items (both immovable or built and movable ones) in Barangay San Agustin, the northernmost barangay 4.5 kms. from the población of this island municipality, famous as the site of the recorded First Mass on Philippine soil by the Magellan expedition in 1521 (Bergreen 2003, 242-254).

While passing by the house of their guide during the barangay tour, he showed the group some artifacts he had stumbled upon while plowing in the family farm during his young years - two small saucers and a tiny pot, all with grayish green color. What particularly caught the author’s attention was that the pot was embossed with what appears to be baybayin characters.

Over the next few years, the author tried to ask from his National Museum contacts about any write-up on the shard, but he did not get much headway. Five years later, the shard was featured again in a published paper with updates on the Intramuros excavation, with matching clear photos (Bautista, et.al., 2015, 45-46). It described that “the ancient inscription was compared with Tagalog and Kapampangan scripts. It can be read tentatively as ‘Palaki’ and interpreted as A la ke (Alay Kay)” (Ibid., 45).

Finally, on 13 October 2015, the author found himself face-to-face with the Intramuros Pot Shard, encased in material that made it appear like a whole pot, which has been displayed at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology, next to the glass display case of the Calatagan Pot. The artifact was not yet there during his previous visit to the museum in June 2015.

ROMAN SCRIPT, NOT BAYBAYIN: The author decided to take the opportunity to look closely at the inscription on the Intramuros Pot Shard while biding time before billeting at a nearby hotel. Somewhat to his disappointment and contrary to his expectation all along, what he found was that the inscription on the shard was not baybayin but crudely-written lower-case Roman letters, which dates it to the Spanish era, and not as ancient as purported. What he deciphered were the following letters: [B]-a-g-t-i-n-g-ue-t-v-v-s-a-n.

The caption for the displayed artifact mentioned that: “Mrs. [EBG], a Cultural Heritage Advocate, compared the script with [T]agalog and [K]apampangan. A tentative deciphering revealed ‘pa-la-ki’ interpreted as ‘a-la-ke’ or ‘alay kay’.” However, the author could not seem to decipher the PA-LA-KI syllables from the script.

Hours later at the hotel, the author used computer blow-ups of his photos to look closer at the inscription on the shard. Only the upper curve of what appears to be capital letter B was visible on the left. He tried to coin words from the deciphered letters and came out with “bagting” or “bagtingi” (from “bagtingue”) and “utusan” or “tuusan.” “Bagting” or “bagtingi” in Bisayan language is to ring (i.e., a bell), but in Tagalog “bagting” is a cord or string for a musical instrument (on-line Tagalog-English translator). “Utusan” in Tagalog is a servant. In Binisayâ, the oldest dictionary (Sanchez 1711) has a word “Tous,” which is the synonym of “pa-id” (i.e., decorum or respect). “Tuusan” would thus mean to show or be shown decorum or respect.

Given the above decipherment and analysis, the author surmised that the Tagalog words “bagting” and “utusan” do not represent the inscription on this artifact with seemingly sacred function.

"RING IT (a bell), NOW RESPECT:" Thereafter, the author concluded that the inscription on the Intramuros Pot Shard is not baybayin but just crude cursive Roman script. The deciphered letters represent two undivided Bisayan words – (B)agtingue [bagtingi; “ring it”] and tvvsan [tuusan; archaic spelling, “show respect”]. In Binisayâ, “(B)agtingi[,] tuusan” literally means “Ring it (a bell), show respect” – which are acts related to the performance of a ritual.

We do not know the full set of acts outlined for the ritual inscribed on the Intramuros Pot Shard and what the ritual was for. The Roman script puts the inscription sometime in the Spanish colonial era, perhaps the 1600s. The artifact suggests the continuity of pot-using rituals that date back from the pre-Spanish era, as represented by the Calatagan Pot. But this time, a Christian bell might have been rung, and no longer the ancient agung or gong.

5. THE LIMASAWA POT

On 11 November 2015, the facilitators of the Cultural Mapping Workshop conducted in Limasawa, Southern Leyte, including the author, joined a local team in their field work to map and document tangible heritage items (both immovable or built and movable ones) in Barangay San Agustin, the northernmost barangay 4.5 kms. from the población of this island municipality, famous as the site of the recorded First Mass on Philippine soil by the Magellan expedition in 1521 (Bergreen 2003, 242-254).

While passing by the house of their guide during the barangay tour, he showed the group some artifacts he had stumbled upon while plowing in the family farm during his young years - two small saucers and a tiny pot, all with grayish green color. What particularly caught the author’s attention was that the pot was embossed with what appears to be baybayin characters.

As an occasional paleographer who had deciphered the ancient baybayin writings on three artifacts now on permanent display at the Baybayin Gallery of the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila (the Calatagan Pot in 2008 and the two Monreal Stones in 2011), the author recognized right away the baybayin characters for MA, WA and BA on the pot. He promptly alerted his fellow facilitators about the significance of this discovery, which could possibly become an equal of the Calatagan Pot, which had been declared a National Cultural Treasure (Borrinaga 2011).

They labelled the artifact as the Limasawa Pot right there and then. After promptly posting its photo on social media, they learned from academician-friends on Facebook that this artifact is a celadon trade ware (green ceramic item) that dates back to the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 A.D.) in China (Bersales 2015, personal communication; Wikipedia). This made the pot between 700 to 1,000 years old.

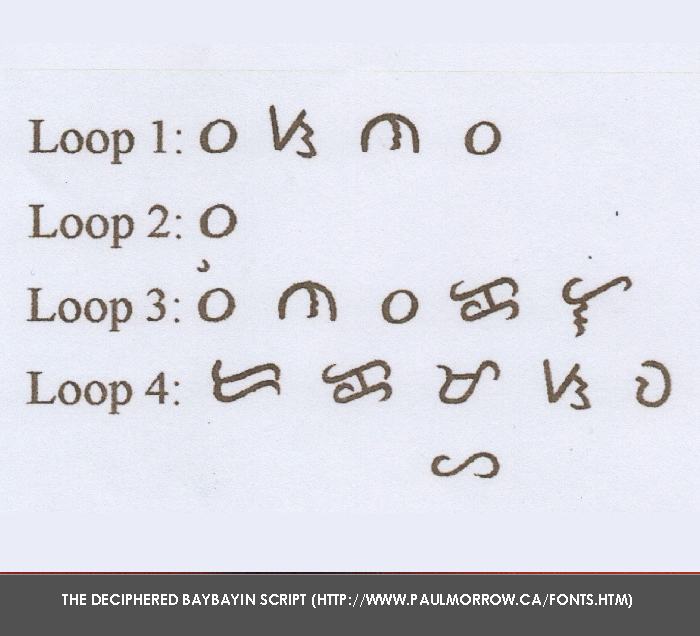

The Limasawa Pot measures 3 inches high and 4 inches in diameter at its widest bulge. Apparently a recycled empty perfume container from China, the pot was embossed with a four-leaf clover design around its mouth, presumably by a native artist, and each of the four loops has writing in baybayin script. The writing is estimated to be at least 500 years old.

It took three weeks of trial-and-error efforts for the author to fully decipher the baybayin writing on the Limasawa Pot, the process details of which are narrated in a paper presented in another national conference (Borrinaga 2016).

The Deciphered Baybayin Script (https://www.paulmorrow.ca/fonts.htm)

Romanized Transcription of the Script

Loop 1: BA – SA – NA – BA

Loop 2: BA – (broken part of pot)

Loop 3: BI - NA – BA – KA – LA[G]

Loop 4: RA – KA[S’] – MA – SA – WA - HA

The Deciphered Baybayin Script (https://www.paulmorrow.ca/fonts.htm)

They labelled the artifact as the Limasawa Pot right there and then. After promptly posting its photo on social media, they learned from academician-friends on Facebook that this artifact is a celadon trade ware (green ceramic item) that dates back to the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 A.D.) in China (Bersales 2015, personal communication; Wikipedia). This made the pot between 700 to 1,000 years old.

The Limasawa Pot measures 3 inches high and 4 inches in diameter at its widest bulge. Apparently a recycled empty perfume container from China, the pot was embossed with a four-leaf clover design around its mouth, presumably by a native artist, and each of the four loops has writing in baybayin script. The writing is estimated to be at least 500 years old.

It took three weeks of trial-and-error efforts for the author to fully decipher the baybayin writing on the Limasawa Pot, the process details of which are narrated in a paper presented in another national conference (Borrinaga 2016).

The Deciphered Baybayin Script (https://www.paulmorrow.ca/fonts.htm)

Romanized Transcription of the Script

Loop 1: BA – SA – NA – BA

Loop 2: BA – (broken part of pot)

Loop 3: BI - NA – BA – KA – LA[G]

Loop 4: RA – KA[S’] – MA – SA – WA - HA

The Deciphered Baybayin Script (https://www.paulmorrow.ca/fonts.htm)

Romanized Transcription of the Script:

Loop 1: BA – SA – NA – BA

Loop 2: BA – (broken part of pot)

Loop 3: BI - NA – BA – KA – LA[G]

Loop 4: RA – KA[S’] – MA – SA – WA

HA

MONOLOGUE LINES OF THE RITUAL PERFORMER: From the above transcription, the author had deciphered the key words bakalág (human sacrifice; Sanchez 1711) and Masáwa (place-name; ancient name of Limasawa) from the baybayin text on the Limasawa Pot. The words suggest the pot’s ritual function and the place where the ritual was performed.

A ritual during the pre-Spanish era and until the Spanish contact was usually officiated by the babaylan, or native priestess. She performed her act in a very theatrical manner, characterized by elaborate costume, dance movements, and acting like in a state of trance (Scott 1994, 84-85), but apparently following a prescribed set of monologue which she presumably elaborated and expanded, depending on the ritual to be performed. In the case of the bakalág ritual, the monologue was outlined by the writing on the Limasawa Pot, as follows:

BISAYAN TEXT:

Basâ na ba?

Ba …

Binabakalá[g]

Ra ka[s’] Masáwa,

ha?

English Translation

Is he already wet?

To be …

Being human-sacrificed

Only you in/for Masawa,

okay?

The first two lines were presumably addressed to the babaylan’s assistant and to the audience-observers of the ritual. The first line presumably asked if the man to be sacrificed had been properly wetted or anointed for the ritual. The missing second line presumably asked if the executioners were ready to perform their assigned task. The last two lines were presumably addressed to the human sacrifice victim. Here, the still-living subject was told in a matter-of-fact manner that he was being sacrificed (binabakalág) in and/or for Masáwa, to which he presumably gave tacit consent.

The monologue might have been followed by the sacrificial act that snuffed out the life of the victim.

The Limasawa Pot appeared to be an essential accessory item in the performance of the bakálag ritual by the ancient Filipinos. It has the written outline of the possible monologue of a babaylan (native priestess) during the ritual. It also became a burial send-off item, presumably at the interment of the sacrificed person afterwards.

In the bakálag ritual practiced by the ancient Filipinos, they brutally sacrificed some slave or captive in the hope that he would be accepted as soul-replacement for that of a sick or dying datu, who they believed was being called away by their ancestor spirits; or as offering at the launching to the sea of their war-boats or large vessels, to invoke luck from their deities (Borrinaga 2016).

CONCLUSION: SURAT BINISAYA:

All the five artifacts featured here, which were discovered in different places and four of which have baybayin writing on them, have texts in Binisayâ or the Bisayan language. By Binisayâ here, the author refers to the Bisayan language of the 1600s or earlier, with archaic words whose old definitions and usage are mostly found in the Vocabulario de la lengva Bisaya by Fr. Mateo Sanchez, S.J. The manuscript of this dictionary was known to have been completed in Dagami, Leyte around 1616 and it was published in Manila in 1711 (Sanchez 1711).

Given the inscriptions on these five artifacts as evidence, it may be concluded that the basic language of the rituals performed by the babaylanes (native priestesses) in pre-Spanish Philippines was Binisayâ or Bisayan until the start of Spanish colonization, when the Latin language of the Christian Mass and rituals were introduced. Not only that, the specific ritual acts of the natives were loosely scripted and their outlines in Binisayâ were inscribed on the artifacts with ancient writing.

The oldest Tagalog dictionary has the word Baibayin translated as “A-b-c,” referring to the native alphabet (San Buenaventura 1613, 627). The equivalent term in Binisayâ is Surat, translated in the oldest Bisayan dictionary by Father Sanchez (1711, 482) as “Letra, o carta, o escrito” (lit., letter [of the alphabet], or mail letter, or written). In this context, from the Bisayan perspective, the baybayin sections of the Doctrina Christiana (Manila 1593) and the UST Baybayin Documents (Jose 2015) would be aptly called Surát Tagalog, because their texts were composed in the Tagalog language and written using the ancient Philippine script. In like manner, the ancient script on the artifacts featured here should be aptly called Surát Binisayâ, because these were composed in the Bisayan language.

During the 1st Philippine Conference on the “Baybayin” Stones of Ticao, Masbate, held in Monreal, Masbate in 2011, the author had proposed the label “Surát Binisayâ” for the written scripts on artifacts with verifiable Binisayâ narratives. The proposal was theoretical at that time. This time, with dictionary proof of the equivalence between the Tagalog term Baybayin and the Bisayan term Surat, he hopes that the label Surát Binisayâ will finally get the acceptance it deserves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT:

This paper was revised from the version presented at the 10th International Conference on Philippine Studies (ICOPHIL-10), held at Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Philippine on 6-8 July 2016. The author received a U.P. Research Dissemination Grant for its writing and presentation. I would like to thank Dr. Francisco A. Datar and Dr. Ricardo Ma. D. Nolasco for including me in the University of the Philippines (UP) team that studied the Monreal Stones. Thanks are also due to Dr. Bernardita Reyes Churchill, President of the Philippine National Historical Society (PNHS) and of the Philippine Studies Association (PSA), for the opportunity to present the Calatagan Pot and Limasawa Pot papers in two PNHS national conferences and this paper at the ICOPHIL-10 sponsored by the PSA.

REFERENCES:

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, SJ. Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas … 1668. Three

books of Part I of the Alcina manuscripts have been translated to English and published. See Kobak, Cantius J., OFM, and Lucio Gutierrez, OP (eds.), History of the Bisayan People in the Philippine Islands (Manila: UST Publishing House). Part I, Book I (Vol. 1) was published in 2002; Part I, Book II (Vol. 2) in 2004; and Part I, Book III (Vol. 3) in 2005.

Arens, SVD, Richard. “Animistic Fishing Ritual in Leyte and Samar.” Leyte-Samar

Studies V (1971): 42-46.

Bautista, Angel P. “Archaeological Excavation at the Iglesia de San Agustin Site,

Intramuros, Manila.” in Lorelei D.C. de Viana (ed.), Manila: Selected Papers of the 18th Annual Manila Studies Conference, August 23-24, 2009 (Quezon City: Manila Studies Association, Inc. and National Commission for Culture and the Arts Committee on Historical Research, 2010), pp. 1-40.

Bautista, Angel P., Orogo, Alfredo B., de la Torre, Amalia, and Mea Karla C.

Dalumpines. “Update on the Archaeological Excavation at Iglesia de San Agustin Site, Intramuros, Manila: Exposition of Archaeological Features and Retrieval of Artifacts and Ecofacts,” in Bernardita Reyes Churchill (issue ed.), Manila: Selected Papers of the 23rd Annual Manila Studies Conference, Teatrillo, Casa Manila, Intramuros, August 7-9, 2014 (Quezon City: Manila Studies Association, Inc. and National Commission for Culture and the Arts Committee on Historical Research, 2015), pp. 30-75.

Bergreen, Laurence. Over the Edge of the World: Magellan’s Terrifying

Circumnavigation of the Globe. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2003.

Bersales, Jose Eleazar R. Personal communication, 2015.

Borrinaga, Rolando O. “Calatagan Pot: The mystery of the ancient inscription.”

Philippine Daily Inquirer, 23 May 2009, A16. (a)

__________. “The 1984 Scott-Kobak Correspondence: A Sharing that Reconstructed

the Sixteenth Century Bisayan Society and Culture,” in Bernardita Reyes Churchill (ed.). The Journal of History LV (2009): 205-225. (b)

__________. “The Calatagan Pot: A National Treasure with Bisayan Inscription.” The

Journal of History LVII (January-December 2011): 54-80. (a)

__________. “Romancing the Monreal Stones: Transcriptions, Decipherments,

Translations, and Some Notes.” Paper presented at the 1st Philippine Conference on the “Baybayin” Stones of Ticao, Masbate, held in Monreal, Masbate Province on 5-6 August 2011. (b)

__________. “The Limasawa Pot: A Bakalág (Human Sacrifice) Ritual Artifact.”

Paper for presentation at 37th National Conference on Local and National

History of the Philippine National Historical Society, Butuan City, October 2016.

Dacanay, Barbara Mae. “Foreign scholars debunk stone tablet with old Philippine

script as modern-day hoax,”

https://gulfnews.com/…/foreign-scholars-debunk-stone-tablet-…. Posted 21 June 2011.

Datar, Francisco A. Personal communication, 2011, 2013.

Doctrina Christiana. Manila, 1593. A fascimile of the copy in the Lessing J.

Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

https://www.geocities.com/gcalla1. Accessed on 21 November 2008. Now a defunct

website, this is the source of the Calatagan Pot photo used here.

https://www.mts.net/~pmorrow/fonts.htm. Accessed on 13 November 2015.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_dynasty. Accessed on 13 November 2015.

Ilagan, Karol. “Calatagan Pot inscription no longer a mystery.” The Daily PCIJ,

https://www.pcij.org/blog/?p=2277. Accessed on 18 November 2008.

Jose, Regalado Trota. “Transcribing the UST Baybayin Documents: Shedding Light

on Early 17th-Century Philippine Writing.” The Journal of History LXII (January-December 2016): 162-185.

Lapeña, Carmela and Howie Severino. “Experts cast doubts on ‘ancient’ baybayin tablet,” https://www.gmanews.tv/print/224011. Posted 21 June 2011.

Morrow, Paul. https://www.facebook.com/pages/Paul-Morrow/112601045446598. The quoted Facebook blog is dated 21 June 2011, at 9:50 a.m. Accessed on 22

June 2011.

__________. “Baybayin – The Ancient Script of the Philippines,” in

https://paulmorrow.ca/bayeng1.htm. Aaccessed on 13 November 2015.

National Museum of the Philippines. Facebook Account, in

www.facebook.com/nationalmuseumofthephilippines. Aaccessed on 13 October 2015.

Nolasco, Ricardo Ma. D. Personal communication, 2011.

Ocampo, Ambeth R. “Tolentino and the Calatagan Pot.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 27

April 2007.

Philippine News.net. “Shard find in Philippines shows an ancient form of writing,” 22

September 2008, in https://www.philippinesnews. net/story/409517. Accessed on 18 November 2008.

San Buenaventura, Pedro de, OFM. Vocabulario de lengva tagala. Valencia: Librerías

“Paris-Valencia,” 1994. Facsimile copy of the one printed in Pila, Laguna by Thomas Pinpin and Domingo Loag, 1613.

Sanchez, SJ, Mateo. Vocabulario de la lengva Bisaya. Manila: Colegio de la

Sagrada Compañia de Jesus, 1711. (Completed in Dagami, Leyte around 1616.)

Santos, Hector. “The Calatagan Pot” (1996), in https://www.bibingka.com/dahon/

/mystery/pot.htm. Accessed on 18 November 2008.

Scott, William Henry. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society.

Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994.

Loop 1: BA – SA – NA – BA

Loop 2: BA – (broken part of pot)

Loop 3: BI - NA – BA – KA – LA[G]

Loop 4: RA – KA[S’] – MA – SA – WA

HA

MONOLOGUE LINES OF THE RITUAL PERFORMER: From the above transcription, the author had deciphered the key words bakalág (human sacrifice; Sanchez 1711) and Masáwa (place-name; ancient name of Limasawa) from the baybayin text on the Limasawa Pot. The words suggest the pot’s ritual function and the place where the ritual was performed.

A ritual during the pre-Spanish era and until the Spanish contact was usually officiated by the babaylan, or native priestess. She performed her act in a very theatrical manner, characterized by elaborate costume, dance movements, and acting like in a state of trance (Scott 1994, 84-85), but apparently following a prescribed set of monologue which she presumably elaborated and expanded, depending on the ritual to be performed. In the case of the bakalág ritual, the monologue was outlined by the writing on the Limasawa Pot, as follows:

BISAYAN TEXT:

Basâ na ba?

Ba …

Binabakalá[g]

Ra ka[s’] Masáwa,

ha?

English Translation

Is he already wet?

To be …

Being human-sacrificed

Only you in/for Masawa,

okay?

The first two lines were presumably addressed to the babaylan’s assistant and to the audience-observers of the ritual. The first line presumably asked if the man to be sacrificed had been properly wetted or anointed for the ritual. The missing second line presumably asked if the executioners were ready to perform their assigned task. The last two lines were presumably addressed to the human sacrifice victim. Here, the still-living subject was told in a matter-of-fact manner that he was being sacrificed (binabakalág) in and/or for Masáwa, to which he presumably gave tacit consent.

The monologue might have been followed by the sacrificial act that snuffed out the life of the victim.

The Limasawa Pot appeared to be an essential accessory item in the performance of the bakálag ritual by the ancient Filipinos. It has the written outline of the possible monologue of a babaylan (native priestess) during the ritual. It also became a burial send-off item, presumably at the interment of the sacrificed person afterwards.

In the bakálag ritual practiced by the ancient Filipinos, they brutally sacrificed some slave or captive in the hope that he would be accepted as soul-replacement for that of a sick or dying datu, who they believed was being called away by their ancestor spirits; or as offering at the launching to the sea of their war-boats or large vessels, to invoke luck from their deities (Borrinaga 2016).

CONCLUSION: SURAT BINISAYA:

All the five artifacts featured here, which were discovered in different places and four of which have baybayin writing on them, have texts in Binisayâ or the Bisayan language. By Binisayâ here, the author refers to the Bisayan language of the 1600s or earlier, with archaic words whose old definitions and usage are mostly found in the Vocabulario de la lengva Bisaya by Fr. Mateo Sanchez, S.J. The manuscript of this dictionary was known to have been completed in Dagami, Leyte around 1616 and it was published in Manila in 1711 (Sanchez 1711).

Given the inscriptions on these five artifacts as evidence, it may be concluded that the basic language of the rituals performed by the babaylanes (native priestesses) in pre-Spanish Philippines was Binisayâ or Bisayan until the start of Spanish colonization, when the Latin language of the Christian Mass and rituals were introduced. Not only that, the specific ritual acts of the natives were loosely scripted and their outlines in Binisayâ were inscribed on the artifacts with ancient writing.

The oldest Tagalog dictionary has the word Baibayin translated as “A-b-c,” referring to the native alphabet (San Buenaventura 1613, 627). The equivalent term in Binisayâ is Surat, translated in the oldest Bisayan dictionary by Father Sanchez (1711, 482) as “Letra, o carta, o escrito” (lit., letter [of the alphabet], or mail letter, or written). In this context, from the Bisayan perspective, the baybayin sections of the Doctrina Christiana (Manila 1593) and the UST Baybayin Documents (Jose 2015) would be aptly called Surát Tagalog, because their texts were composed in the Tagalog language and written using the ancient Philippine script. In like manner, the ancient script on the artifacts featured here should be aptly called Surát Binisayâ, because these were composed in the Bisayan language.

During the 1st Philippine Conference on the “Baybayin” Stones of Ticao, Masbate, held in Monreal, Masbate in 2011, the author had proposed the label “Surát Binisayâ” for the written scripts on artifacts with verifiable Binisayâ narratives. The proposal was theoretical at that time. This time, with dictionary proof of the equivalence between the Tagalog term Baybayin and the Bisayan term Surat, he hopes that the label Surát Binisayâ will finally get the acceptance it deserves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT:

This paper was revised from the version presented at the 10th International Conference on Philippine Studies (ICOPHIL-10), held at Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Philippine on 6-8 July 2016. The author received a U.P. Research Dissemination Grant for its writing and presentation. I would like to thank Dr. Francisco A. Datar and Dr. Ricardo Ma. D. Nolasco for including me in the University of the Philippines (UP) team that studied the Monreal Stones. Thanks are also due to Dr. Bernardita Reyes Churchill, President of the Philippine National Historical Society (PNHS) and of the Philippine Studies Association (PSA), for the opportunity to present the Calatagan Pot and Limasawa Pot papers in two PNHS national conferences and this paper at the ICOPHIL-10 sponsored by the PSA.

REFERENCES:

Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, SJ. Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas … 1668. Three

books of Part I of the Alcina manuscripts have been translated to English and published. See Kobak, Cantius J., OFM, and Lucio Gutierrez, OP (eds.), History of the Bisayan People in the Philippine Islands (Manila: UST Publishing House). Part I, Book I (Vol. 1) was published in 2002; Part I, Book II (Vol. 2) in 2004; and Part I, Book III (Vol. 3) in 2005.

Arens, SVD, Richard. “Animistic Fishing Ritual in Leyte and Samar.” Leyte-Samar

Studies V (1971): 42-46.

Bautista, Angel P. “Archaeological Excavation at the Iglesia de San Agustin Site,

Intramuros, Manila.” in Lorelei D.C. de Viana (ed.), Manila: Selected Papers of the 18th Annual Manila Studies Conference, August 23-24, 2009 (Quezon City: Manila Studies Association, Inc. and National Commission for Culture and the Arts Committee on Historical Research, 2010), pp. 1-40.

Bautista, Angel P., Orogo, Alfredo B., de la Torre, Amalia, and Mea Karla C.

Dalumpines. “Update on the Archaeological Excavation at Iglesia de San Agustin Site, Intramuros, Manila: Exposition of Archaeological Features and Retrieval of Artifacts and Ecofacts,” in Bernardita Reyes Churchill (issue ed.), Manila: Selected Papers of the 23rd Annual Manila Studies Conference, Teatrillo, Casa Manila, Intramuros, August 7-9, 2014 (Quezon City: Manila Studies Association, Inc. and National Commission for Culture and the Arts Committee on Historical Research, 2015), pp. 30-75.

Bergreen, Laurence. Over the Edge of the World: Magellan’s Terrifying

Circumnavigation of the Globe. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2003.

Bersales, Jose Eleazar R. Personal communication, 2015.

Borrinaga, Rolando O. “Calatagan Pot: The mystery of the ancient inscription.”

Philippine Daily Inquirer, 23 May 2009, A16. (a)

__________. “The 1984 Scott-Kobak Correspondence: A Sharing that Reconstructed

the Sixteenth Century Bisayan Society and Culture,” in Bernardita Reyes Churchill (ed.). The Journal of History LV (2009): 205-225. (b)

__________. “The Calatagan Pot: A National Treasure with Bisayan Inscription.” The

Journal of History LVII (January-December 2011): 54-80. (a)

__________. “Romancing the Monreal Stones: Transcriptions, Decipherments,

Translations, and Some Notes.” Paper presented at the 1st Philippine Conference on the “Baybayin” Stones of Ticao, Masbate, held in Monreal, Masbate Province on 5-6 August 2011. (b)

__________. “The Limasawa Pot: A Bakalág (Human Sacrifice) Ritual Artifact.”

Paper for presentation at 37th National Conference on Local and National

History of the Philippine National Historical Society, Butuan City, October 2016.

Dacanay, Barbara Mae. “Foreign scholars debunk stone tablet with old Philippine

script as modern-day hoax,”

https://gulfnews.com/…/foreign-scholars-debunk-stone-tablet-…. Posted 21 June 2011.

Datar, Francisco A. Personal communication, 2011, 2013.

Doctrina Christiana. Manila, 1593. A fascimile of the copy in the Lessing J.

Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

https://www.geocities.com/gcalla1. Accessed on 21 November 2008. Now a defunct

website, this is the source of the Calatagan Pot photo used here.

https://www.mts.net/~pmorrow/fonts.htm. Accessed on 13 November 2015.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_dynasty. Accessed on 13 November 2015.

Ilagan, Karol. “Calatagan Pot inscription no longer a mystery.” The Daily PCIJ,

https://www.pcij.org/blog/?p=2277. Accessed on 18 November 2008.

Jose, Regalado Trota. “Transcribing the UST Baybayin Documents: Shedding Light

on Early 17th-Century Philippine Writing.” The Journal of History LXII (January-December 2016): 162-185.

Lapeña, Carmela and Howie Severino. “Experts cast doubts on ‘ancient’ baybayin tablet,” https://www.gmanews.tv/print/224011. Posted 21 June 2011.

Morrow, Paul. https://www.facebook.com/pages/Paul-Morrow/112601045446598. The quoted Facebook blog is dated 21 June 2011, at 9:50 a.m. Accessed on 22

June 2011.

__________. “Baybayin – The Ancient Script of the Philippines,” in

https://paulmorrow.ca/bayeng1.htm. Aaccessed on 13 November 2015.

National Museum of the Philippines. Facebook Account, in

www.facebook.com/nationalmuseumofthephilippines. Aaccessed on 13 October 2015.

Nolasco, Ricardo Ma. D. Personal communication, 2011.

Ocampo, Ambeth R. “Tolentino and the Calatagan Pot.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 27

April 2007.

Philippine News.net. “Shard find in Philippines shows an ancient form of writing,” 22

September 2008, in https://www.philippinesnews. net/story/409517. Accessed on 18 November 2008.

San Buenaventura, Pedro de, OFM. Vocabulario de lengva tagala. Valencia: Librerías

“Paris-Valencia,” 1994. Facsimile copy of the one printed in Pila, Laguna by Thomas Pinpin and Domingo Loag, 1613.

Sanchez, SJ, Mateo. Vocabulario de la lengva Bisaya. Manila: Colegio de la

Sagrada Compañia de Jesus, 1711. (Completed in Dagami, Leyte around 1616.)

Santos, Hector. “The Calatagan Pot” (1996), in https://www.bibingka.com/dahon/

/mystery/pot.htm. Accessed on 18 November 2008.

Scott, William Henry. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society.

Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994.